The Social and Cultural History of Blood as Food in Ireland and its Role in the Formation of Identity for Clonakilty Blackpudding.

Reference Number: FL6802 – 115141319

Reference Number: FL6802 – 115141319

Reference Number: FL6802 – 115141319

This mini thesis was written as part of my final research project and assessment in the Food, Festival and Folklore module of the Postgraduate Diploma in Irish Food Culture. It was submitted on 25th May, 2021.

Following this research project, I was commissioned to write about black pudding culture in Ireland for Vittles in the UK. The essay was called: The Aleph, A Story of Irish Food in One Pudding. You can access this essay HERE. The beautiful illustration at the top of this blog post was created by Alia Wilhelm especially for my Vittles essay. You can follow Alia here, and subscribe to Vittles here.

I intend to extend my research into blood pudding in Ireland over the coming months and years, as well as relishing opportunities to speak more on my research in many different ways. As I do, I will add them to The Flavour Files.

ABSTRACT

The presence of blood as food in the cultural and social history of Ireland is a prism through which shifts in competing worldviews can be observed. In the practice, preparation, and consumption of blood as food, it has been a food of high value and good economic sense, but also isolated by colonial propagandists to ridicule and intentionally misrepresent as a weapon of suppressive control. Black pudding, the most familiar form of blood as food in Ireland, was traditionally the output of women’s work on subsistence farms, the sale of which generated income and a way for women to assert autonomy in a patriarchal culture. Contemporary production of blood pudding is removed from the domestic sphere and the work of women into the commercial sphere and the work of men, a contextual change that enabled another shift in worldview of blood as food: its elevation from the ordinary to the extraordinary. This research project demonstrates the importance of blood as food in the social and cultural history of Ireland; how different, often conflicting, worldviews change the perception of it at different points in time, and the role of women making food from blood and its utility in personal autonomy. A Case Study on Clonakilty Blackpudding illustrates how these influences were key in the formation of an identity for a product and a brand, and in creating a contemporary alternative worldview of blood as food in Ireland.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Regina Sexton: an unending source of knowledge, a grounding influence, and a challenger of ideas. Thanks also to Hugh Maguire and Micheál ‘Haulie’ O’Neill for their insights into the tradition of black pudding making in Ireland. Con McCarthy of The Michael Collins Centre, Cal McCarthy and Jamie Murphy of Michael Collins House Museum, James Langton of the Collins 22 Society for their insights into rural life in West Cork between 1880 and 1920. Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, Kieran McCarthy and Donagh O’Reilly in relation to the meat producing history of Cork city. Kieran Doyle, Carmel Flahavan, Tomás Tuipéar for their insights into local food culture and commerce of Clonakilty. John McKenna for his critique of the Irish food movement in the 20th century.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This research began with a question: What makes Clonakilty Blackpudding so special? In searching for an answer, I found that Irish cultural and social history is intimately connected to a practice of consuming blood as food, and in the many ways blood was harvested, prepared, cooked, eaten, and shared. Blood as a source of food has been celebrated, derided, considered a last resort, forgotten, revived and, (completing the circle), is a celebrated food of Ireland once more. Through my research, I found this complex, evolving relationship of blood as food in Ireland connected to identity. Analysing this connection of food and identity, I consider the impact of conflicting worldviews on the practice of blood as food from within and without Ireland.

I also examine the role of women, blood, and food in the domestic sphere, specifically the production of black puddings, and how that industry afforded a route to personal autonomy through trade in excess puddings for pin money. As pudding production is removed from the domestic sphere into the commercial sphere, I examine how women are erased from the narrative of pudding making, and the autonomy that afforded, in parallel with a changing food culture that is eager to disregard traditional foods in favour of those in step with modernity.

My Case Study begins when Ireland’s food culture is fractured and old foodways are disappearing. I focus on the work of Edward Twomey, late of Clonakilty Blackpudding, who recognised the humble black pudding and its links with history, social and cultural practice, tradition, ingredients, and bonded it to a quasi-mythic tale of one woman and her unchanged secret recipe for black pudding. Such action was symbolic in returning women as central to the story of blood as food in Ireland while simultaneously manipulating that symbology for commercial gain.

My research has centred on accounts of people, past and living. There is little published academic work on blood as food in Ireland, or the important role women had in producing food from blood. To this end, my primary text is A. T. Lucas’s collection of essays Cattle in Ancient Ireland (1989), a body of research spanning almost 30 years.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Two main challenges are present in the available literature on blood as food in Ireland. Firstly, little is published; secondly, the majority of what is written has been scripted or collected by men to which the issue of gender bias in what is recorded and chosen for observation and critique must be acknowledged. In my introduction, I assert women and the practice of blood as food are connected, not only in preparation and cooking, but also because, as my Case Study will demonstrate, contemporary commercial black pudding production originated with women.

My primary text is Cattle in Ancient Ireland (Lucas, 1989), specifically the essay Blood as Food. The essay focuses on the custom and practice of live bleeding of cattle in Ireland between 15th and 19th centuries. Within are accounts collected by Lucas focus on the live bleeding itself and then consuming blood harvested in this way, all have been written by men. Details on how blood was made into food “is scanty enough,” (Lucas, 1989), and probable that this work is overlooked without intention but indicative of systemic undervaluing of women and their work. An absence of interest in cookery transforming the taboo rawness of blood into food to eat does, however, work in the writer’s favour allowing readers to imagine the baseness of how blood is consumed; that raw food requires little skill, that the Irish do not possess skills for cookery, and plays to animalistic imagery of eating blood.

I ran search terms through the Main Manuscripts Collection and the School’s Collection online, but the return of results less in number and diversity than I anticipated. Below is a table showing the search terms and summary returns:

| Search Term | # Entries | Topic Headings | Observations |

| Black pudding | 9 | Funny Stories, Care of Animals, Rhymes, Riddles | 1 entry for black pudding as food, under Social. |

| Blood pudding | 9 | Blood Pudding, How we make Blood Pudding, Dishes Not Now Made, Food in Olden Times, Social | All entries relate to the preparation of blood puddings. Only two accounts by females provide detail on the process of making blood puddings from killing the pig to boiling puddings in a pot. |

| Blood | 9,216 | Cures, Stories, Food, How to Make Rubber, Religion, Local Customs, Beliefs, etc. | In comparison to entries for black pudding and blood pudding, the frequency of accounts on the importance of blood in folklore, customs, and beliefs support my argument that use of blood as food from the 19th century onwards declines considerably as traditional Irish food culture is replaced with a food culture aligning with modernity. |

In contrast to the detailed accounts of blood as food by outsiders (Lucas, 1989), and the lack of detailed accounts of blood as food in the National Folklore Collection, two books written by women about women, The Women (Taylor, 2015) and Women Speak (Wickham, 2013), provide details accounts by ordinary women of the activities on the day a pig is slaughtered, and puddings made. The accounts depict the gravitas of the day and the communality; but it is how the work of the women and the deference bestowed upon the woman of the house, and her recipe for puddings made from the blood of her pig, that illustrates a hierarchy among women and mutual respect for the home they were in, the recipe used, and the woman at the centre of it all.

A general absence of sources on the social and cultural history of blood as food in Ireland reflects a general lack of academic interest. However, through interview research I discovered that there is still a rich hive mind of recollection, memory, stories, and skill that is extant in the living memories of people today, but that this knowledge is under threat from the advancement of time. The collection of these accounts of people who remember blood pudding making at home are ripe for research, and necessary before they are lost forever.

METHODOLOGY

I applied a qualitative approach to my research for this paper. I collected and collated information from multiple sources and conducted analysis to identify common and/or reoccurring themes. I established a historical timeline of key events for indications of correlating changes in social and/or cultural behaviour. The analysis was overlayed and evaluated for evidence that may support or disproved my hypothesis.

A dearth of primary source material relating to my area of research and Covid-19 restrictions on in-person access to archive and manuscript materials necessitated the employment of multiple methods of research as was available, including materials available online from reputable and reliable sources, such as the UCC online library, Duchas.ie and local history groups.

14 individual informal interviews were conducted by telephone and online meetings with follow up email communications. Interviews encompassed topics across my research area including farming, butchery, commercial pudding making, historical aspects of rural and urban life; the meat trade through time in Ireland, the role of women in food, food in Ireland in 19th and 20th centuries, and recollections of pudding making in childhood.

DATA ANALYSIS

The use of blood as food is not unique to Ireland. In medieval Europe it was “not uncommon for even poor families to own a pig, which was slaughtered in autumn”, (Davidson, 1999), after the pig had fattened on the abundance of autumn mast, to preserve winter fodder store, becoming food itself, and the blood from slaughtered pigs used to make well-known puddings of France, Spain, UK, and also Ireland. Such ubiquity raises the question: where does the modern perception of blood and black pudding as a traditional food of Ireland originate? The practice, utility, consumption, and attitude towards blood as food in Ireland evolves in the social and cultural context, particularly in relation to observations of the Irish peasant diet by aristocratic ‘travellers’ – commentators working on behalf of the British government with a vested interest in dehumanising the Irish for purposes of dominion and control. By mid to late twentieth century, a revival in interest of Irish food emerges, particularly cookery books specialising in Irish ingredients and recipes.In the past half a century, black pudding is a popular food once more transcending social class, equally at home on breakfast plates, fine dining menus, and everything in between.

This essay examines the social and cultural history of blood as food in Ireland, the impact of outside influences on the indigenous practice of consuming blood as food, and the role of men and women in domestic and commercial spheres on producing food from blood. A case study demonstrates this social and cultural history of blood as food in Ireland in the formation of identity for Clonakilty Black Pudding, one of Ireland’s most enduringly popular black pudding brands.

Blood as Food in the Historical Record

Blood as food in Ireland is represented in historical texts as early as the 11th century Aislinge Mac Con Glinne, (Meyer, 1892). The poem is an elucidation of the land of plenty genre, (Sexton, 1995), a fantastical land made of food. Potential descriptors of blood as food include “fresh boiled puddings” although does not definitively suggest blood pudding, as the description of “twenty-nine fair puddings of white-fat cows,” infers; but if we infer blood, note puddings are made from the blood of cattle. In “Blood as Food”, (Lucas, 1989), focus is on the practice of live bleeding cattle between the sixteenth and nineteenth century when Lucas suggests the practice disappears from record. The practice of live bleeding cattle is one of good sense to subsistence farmers: cattle were more valuable alive than dead for their supply of bán bidh, or white meats. The Corpus Iuris Hibernica, (Binchy, 1978), codified food for payment of rents, tithes, and restitution, and underpined hierarchical protocols of hospitality. The eating of meat was reserved for upper classes, bullocks were “surrendered as part of the food rents between farmers and landlords,” (Sexton, 1998), and so consumption of blood represents one small way the peasantry could access flesh meat.

It is unclear from accounts in Lucas’s essay whether this practice of live drawing of blood was used on cows in general, as the term cattle is generally taken to refer to beef cows rather than milch cows, however the account of the Rev. Philip Skelton in 1757 in Blood as Food states: “thus the same cow often afforded both milk and blood.”[1] This clearly suggests live bleeding was practiced on milch cows as a renewable source of food without resorting to slaughter until the cow became unproductive in the supply of milk (Lucas, 1989). Blood is a source of fresh meat and nutritious marking it out as food of great economy, healthfulness, and immense enjoyment. The introduction to Cattle in Ancient Ireland, (Lucas, 1989), notes the “thousands of allusions are not to cattle in general but specifically to cows and more specifically to cows as yielders of milk.”[2] However, turmoil exerted in the years leading up to and immediately following reformation of the cattle trade in Ireland, culminating in The Cattle Act of 1666, suggests that while milk remained a valuable source of food in the domestic sphere, in the commercial sphere focus was ever more on rearing of beef cattle for export to England. Following imposition of the 1666 Act and catastrophic loss of trade that resulted, a root and branch remodelling of Ireland’s cattle economy took place – Ireland was no longer just a cattle breeding colony, but a powerhouse of breeding, fattening, and processing of cattle creating a booming industry provisioning ships with salted meats. (Murray, 1907; Edie, 1970; Sexton, 1995; Collingham, 2017).

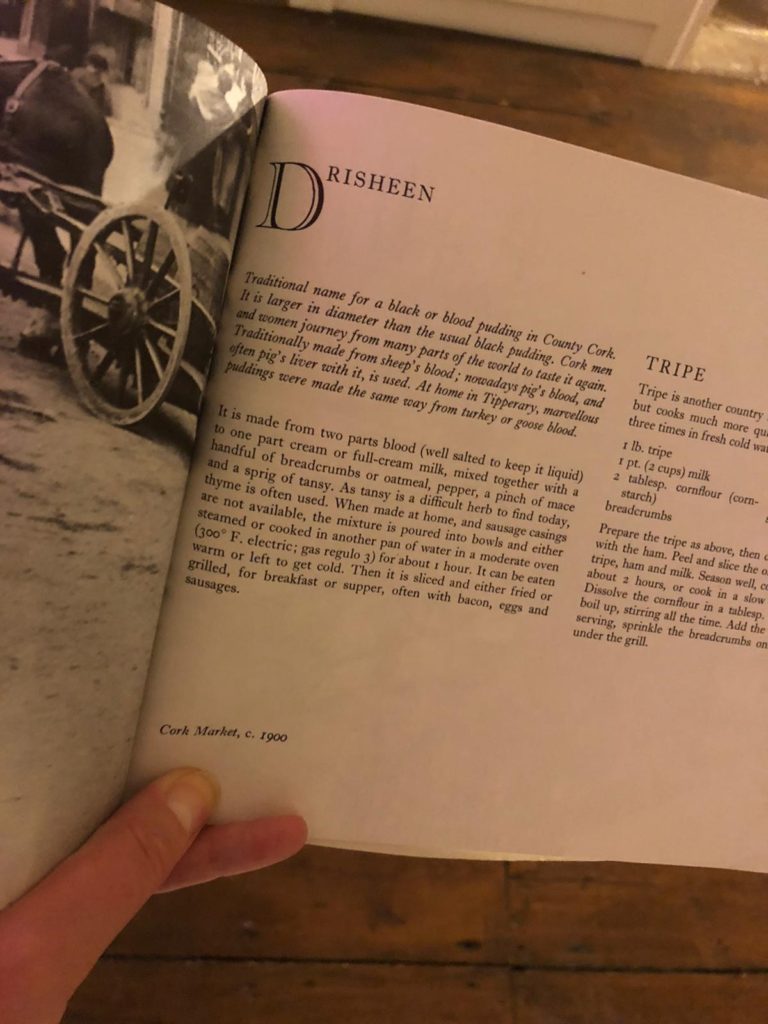

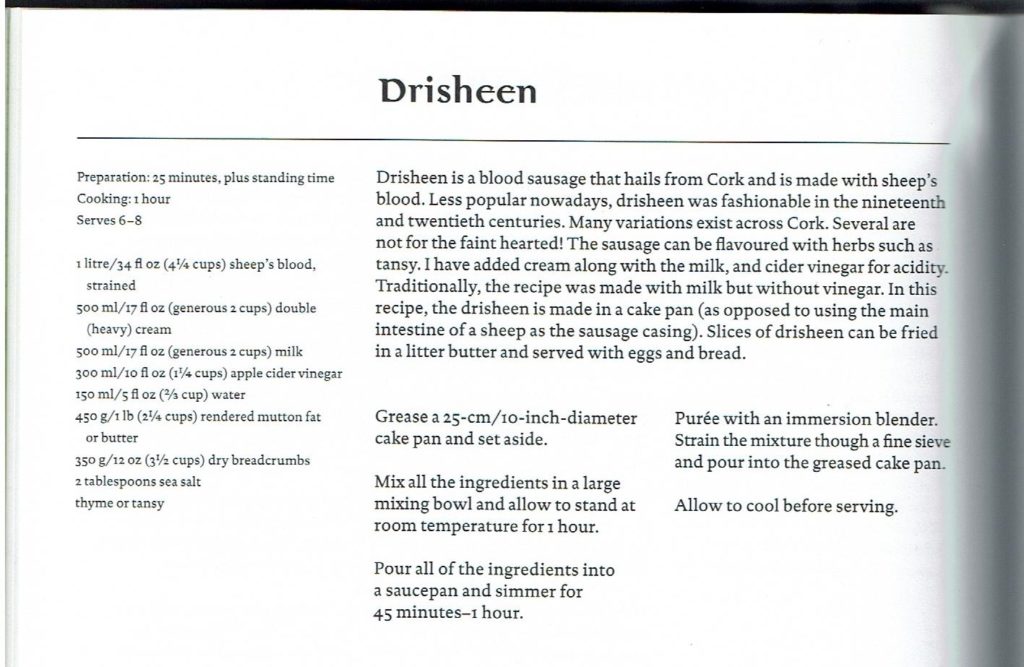

From herein emerges a consistent record of blood as food in the urban context, as well as the rural. Cork was at the centre of the provisions trade between 1680 and 1825, and in 1776 “109,052 barrels of salted beef were delivered annually to ports in England, Europe and as far away as the West Indies and Newfoundland”, (Sexton, 1995), representing 60% of the full Irish export total (McCarthy, 2016). Such was the level of animal slaughter in the city it earned the monikers “the Slaughterhouse of Ireland” and “the Ox-slaying City of Cork” (Sexton, 1995). But for all the beef processed in the city, offal and blood were foods of the poorer classes, and drisheen, a blood pudding made with beef and sheep’s blood and sometimes flavoured with the wild herb tansy, ever since considered “the blood pudding of Cork” (Sexton, 1995).

Throughout this time, reports on consumption of blood as food by the Irish poor, particularly in rural settings, are published fomenting a perception of the Irish as savage and uncivilised. Sexton (2018) refers to the traditional Gaelic food culture as one that “was systematically denigrated by commentators and propagandists for the crown. Gaelic food practices were described in blanket tones of stock, revulsion and disgust […] Presented as primitive, disordered and unhygienic, the food culture of Gaelic Irish became a convenient symbol with which to represent the general disarray and barbarity of ‘the other’.” These reports were taken out of the social and cultural context of harvesting blood, the many ways eaten, and its high regard among the rural Irish peasantry for its enjoyable taste. A dearth of contextualisation disregards the economic situation of the rural Irish and the healthfulness of blood as food. One recorder less prejudicial, John O’Donovan in 1834, working in Ireland for the Ordnance Survey[3], wrote describing the use of blood as “not through necessity, but as a luxury”, furthermore: “it was irrational to allow the use of the blood of a dead animal as food and object to the use of the blood of a living one,” (Lucas, 1989).

When Worldviews Collide

In Lucas’ examination of blood as food in Ireland, he presents a collision of competing worldviews. On one hand, the Irish worldview of blood as food is regenerative, economical, nutritious, delicious; a source of fresh meat that is free of the taste of salt, and versatile in how it can be prepared, cooked, flavoured, and served. On the other, the outsider’s worldview of blood as food is one of animalistic behaviour, visceral, raw, of last resort, lacking skill, an opposite exclusionary worldview.

O’Donovan’s 1834 letter (Lucas, 1989) acknowledges his own personal prejudice in observing the practice, and notes that it is “considered a great luxury by the mountaineers,” that “The cattle are improved, not injured by being thus bled,” and that “the blood is sufficiently boiled, it is taken up and mixed with butter, and variously prepared according to the taste and knowledge of the cook.”[4] This account stands out from other commentators as O’Donovan took care to observe the customs surrounding harvesting, cooking, and eating blood, acknowledges his own bias in his reaction to the practice, and locates it in the context of the Irish worldview when he says: “the people are not only not ashamed of it, but unwilling to discontinue it, because they insist that it is perfectly civilised and proper.” The author does not associate the practice with food of last resort; in fact, the opposite view is presented.

Proactive attempts to undermine the Irish worldview, to displace it, is a form of colonisation; the danger being “when the worldview changes, everything changes […] changed circumstances can destroy or displace a worldview, and once this happens, the old worldview no longer holds sway for society” (R. Kingston, lecture notes, 4th May 2021). The reportage of propagandist travellers for the British Crown for nearly 400 years ends towards the end of the 19th century when accounts of live cattle bleeding begin to die out (Lucas, 1989). One inference is a correlation between the shaming of Irish food culture by the British during colonialisation and practices such as live bleeding ceasing, but a typical subsistence Irish farmer would not have read these publications and therefore not privy to their insults and insinuations. It is more likely a consequence of Ireland rapidly changing in multiple ways after the Great Famine: one million Irish deaths and, in following years, an estimated two million emigrated representing a loss of collective, indigenous knowledge, social and cultural practice that contributed to the traditional Irish worldview of blood as food. It takes skill to use a ‘flame’, the tool for bleeding a live animal, and possible that those who could died or fled in the famine years. It may also explain why, as accounts of live bleeding of cattle diminished, the use of pig blood in the domestic sphere for pudding making becomes dominant in accounts and in memory.

At the turn of the 19th century, Ireland was a changing, modernising country with increasing trade, and better education for children, and the fight for Irish independence growing apace. Ireland is at a crossroads of defining a new identity for itself as an independent sovereign nation, and in the milieu, tension builds between old traditional Ireland and new modern Ireland. In contrast to previous ‘travellers’, English writer, H. V. Morton, in his travelogue In Search of Ireland, (Morton, 1930), is open to understanding the Irish worldview:

“We in England have almost as much to forget about Ireland as she has to remember about England. We must forget hosts of prejudiced, and often ludicrous, ideas about her and her people, which have accumulated during many centuries of strife and misunderstanding […]”[5]

Later, Morton recalls a derisory response to his request of drisheen for breakfast at an Irish hotel[6]:

“When I asked in the hotel for ‘drisheen’ they thought that I was trying to be funny. They treated me to that snobbish amusement which the Ritz would bestow on a man who was honest enough to demand a black pudding or a pound of tripe. This drisheen, which looks like a large and poisonous snake, is a native of Cork […] But drisheen is above such low comment: one might call it the caviare of Cork. […] In a moment of mistaken enthusiasm they poured melted butter on it, but I felt instinctively that drisheen lovers employ a less sickly garnish. It is a peculiar, subtle dish, pleasant and ladylike. I believe that I would have liked it better fried.”

This quote illustrates the new emerging worldview of the Irish to its own native food. Where once it was derided by outsiders, now the Irish themselves contemptibly view drisheen as synonymous with reduced means and opportunity. Thus, the Irish worldview of its tradition of consuming blood as food has been entirely displaced at a time when the country itself is establishing a new identity as a Free State[7].

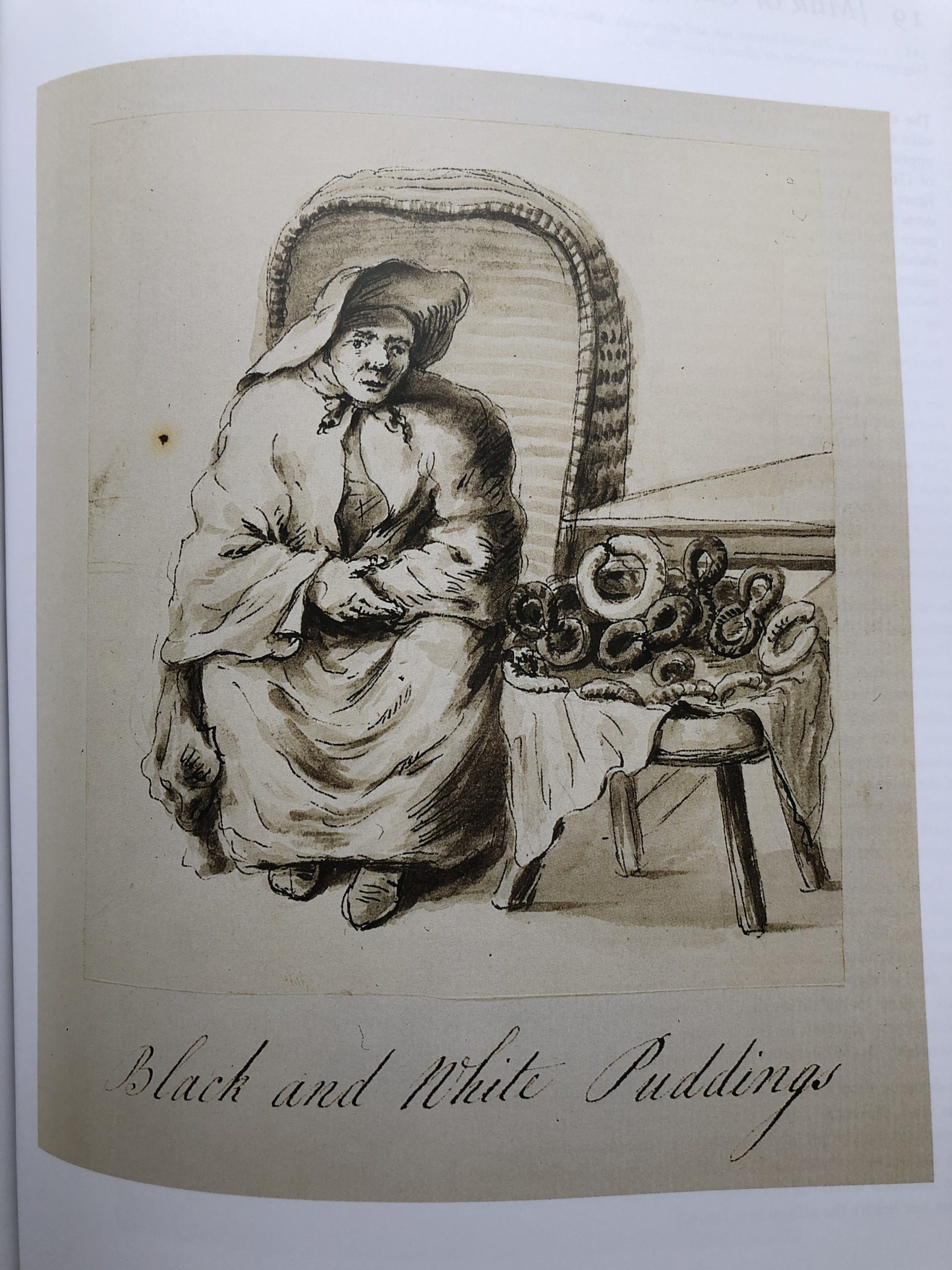

There emerges a clearer distinction between the way blood is utilised in food in the urban-commercial and rural-domestic setting. Blood puddings in the urban context are depicted in a collection of illustrations drawn in 1760 by Hugh Douglas Hamilton titled The Cries of Dublin (2003) of hawkers selling wares on Dublin streets, and literally draws women into the industry of food production. Plate 18[8] “Black and White Puddings” depicts a female hawker selling black and white puddings. Although not explicit, reports Lucas cites in his essay establishes a delineation of roles in harvesting blood (men) and turning it into food to eat (women), whether baked, mixed with oats, flavoured with herbs, or other types of relish or ‘kitchen’, or boiled into puddings[9]. This further undermines observations of British ‘travellers’ of blood eaten raw – in fact, there was industry in preparing and cooking the blood in such a manner, and that it was good enough to trade with. It is by this industry of women that the practice of blood as food transcends the rural-domestic sphere and appears in the urban-commercial sphere, and places women at the centre of the discussion of blood as food, and how this industry attributed to the personal autonomy of Irish women.

The role of women in producing food from blood

The historical records and accounts encountered so far downplay the important role women had in the domestic economy and does little to illustrate their important contribution to the social and cultural history of blood as food in Ireland. Dairying, butter making, eggs, meat preservation (cleaning, salting, barrelling, and pudding making), and cooking were all considered women’s work, ensured sufficient food to last the winter, and endowed significantly to the domestic purse. Lucas (1989) admits that “the information at our disposal about the preparation of the blood for food is scanty enough” and is left having to draw “from what is known about other aspects of the Irish diet.”[10] There are grounds to presume bias as the justification for this as only men are writing about food amongst the Irish poor. Accounts in the National Folklore Commission (NFC) Manuscripts Collection into these important, vernacular activities details are minimal, so we must look elsewhere – in memory of those who participated in or witnessed the practice. This account of Margaret Feen recorded in Wickham (2013) of growing up in 1920’s Clonakilty recalls her mother making puddings:

“A great number of people never tasted meat, but farmers usually cured their own bacon and what a treat it was when the pig was killed and the delectable fresh pork and pork steak was so enjoyed. […] My mother filled the puddings, after thoroughly washing them, with a mixture of oatmeal, onions, salt and pepper and blood then boiled them in the big pot with hay in the bottom to prevent burning. They were so delicious and they were shared with the neighbours.”[11]

The female perspective of pudding making evokes a more convincing social and cultural history than the insular male perspective of accounts in Lucas’s essay as illustrated by this excerpt from The Women, (Taylor, 2015):

“Dealing with the dead pig was a communal affair. Neighbouring women came together to fill the sausages and puddings and each had a different recipe, but the recipe of the woman of the house prevailed at her pudding filling. We all enjoyed savouring the different flavours throughout the year. Filling the puddings, as it was called, took over the whole house, with disgusting-looking buckets of pig’s guts standing all around the kitchen, as well as enamel buckets full of boiled blood laced with herbs and all kinds of mysterious concoctions. There was a black-pudding mix and a white-pudding mix. It was a messy business, but finally the mixture was pushed into a mincer to which a funnel was attached, and over this went the pig’s well-washed gut, which was then filled with the mixture. It came out in long, thick tubes, and my mother cut it as intervals into loops, then plunged them into a pot of boiling water that stood on the open fire. Then she filed them along the handle of a brush until they cooled. Nowadays we can buy the world-famous Clonakilty black pudding in most supermarkets, but it all began with the resourceful women in the farmhouses of rural Ireland. Preserving every bit of food the pig supplied was most important. Fresh pork steaks as well as the home-filled sausages and puddings were distributed among the neighbours, who returned the compliment when their pig was slaughtered. Thus, fresh meat as had more often throughout the community.”

This domestic industriousness Taylor refers did not end with making blood pudding and sharing with neighbours: excess puddings were sold to butchers or hawked on the street, like the scene captured in the Cries of Dublin. The practice of selling excess produce, such as eggs, butter, and puddings is referred to colloquially as egg or pin money and marked these foods as tradeable – valuable, not just to the farm as housekeeping, but also for women who had little status and money of their own.

Most households, urban and rural, owned a pig reared for meat and slaughtered after fattening on autumn mast (T. Tuipéar, pers. comms., 27th January 2021[12]). A modern pig provides on average three litres of blood[13](H. Maguire, pers. comms., 11th January 2021[14]) yielding around 12 puddings tied into rings[15], a source of fresh meat eaten within a couple of weeks of making, often shared between neighbours who may have helped during the day. Accounts in the NFC are not definitive as to when after slaughter puddings were made, fluctuating between hours and days possibly dependent upon how much help was on hand, and priority given over to preparing, salting, and barrelling the meat. Blood was salted and stirred to prevent coagulation then set aside while the delicate work of cleaning the intestine, (also referred to as ‘the pudding’[16]) was completed. The blood is then mixed to a recipe which may include grain, (oatmeal or rice), onions, salt, spices, milk, and pork fat; the cleaned intestines then filled, tied, and cooked in water below the boil to prevent bursting. Children were part of the day’s labour too, one account recalled running away and hiding in the trees away from the squeals of the pig as it was trussed ready for slaughter (P. Ryan, pers. comms., 1st March 2021[17]). Aside from the horror and gore associated with the day, accounts focus on communality and the anticipation of eating fresh meat[18], slices of black pudding cooked in lard (possibly bacon fat), and served with a small piece of fresh pork steak – a rare and delicious treat; while an account in the NFC stated: “When we sit at the table and get a plate of pork or rashers or black pudding & sausages before us do we ever think of the poor old pig that we never think about.”[19]

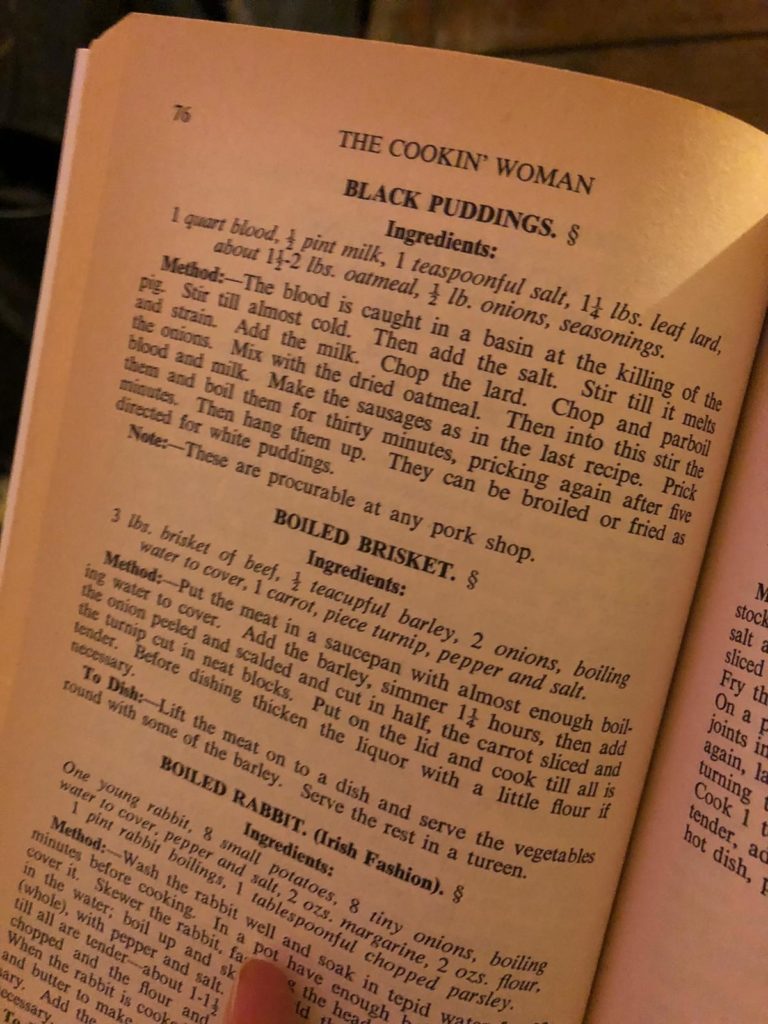

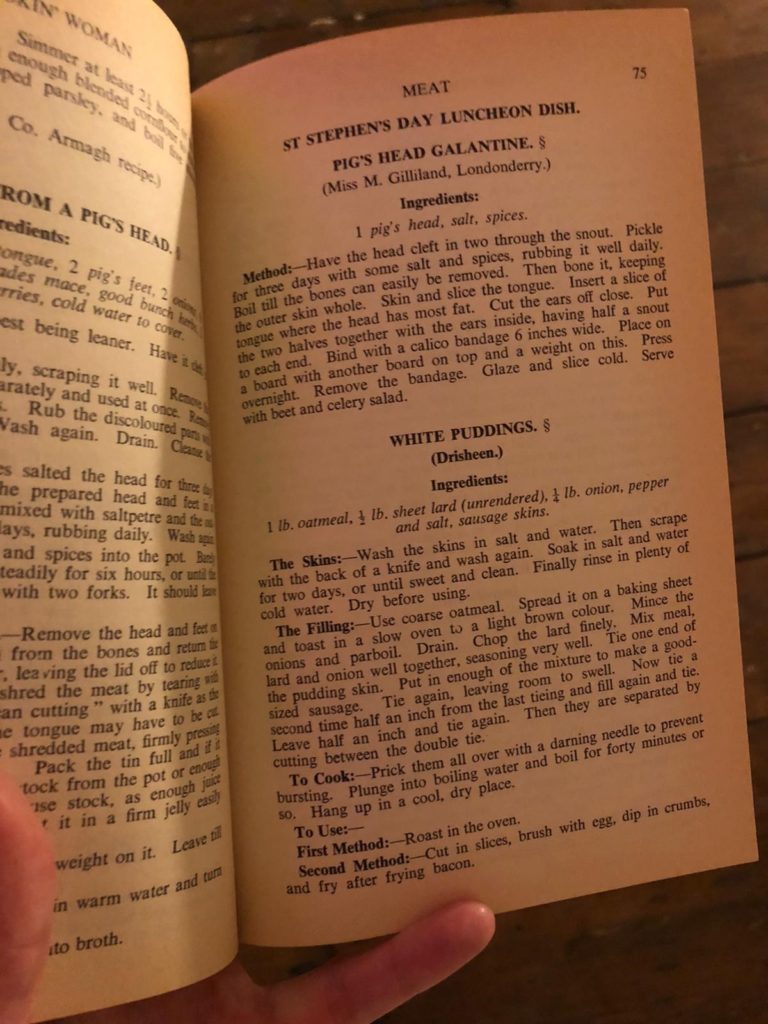

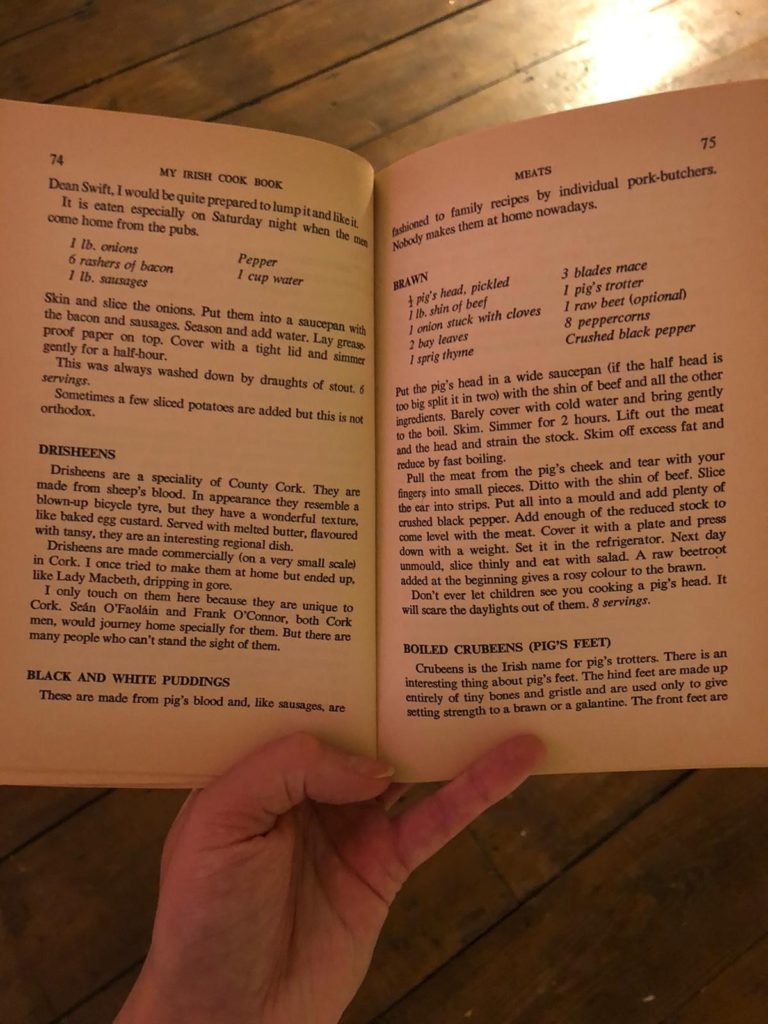

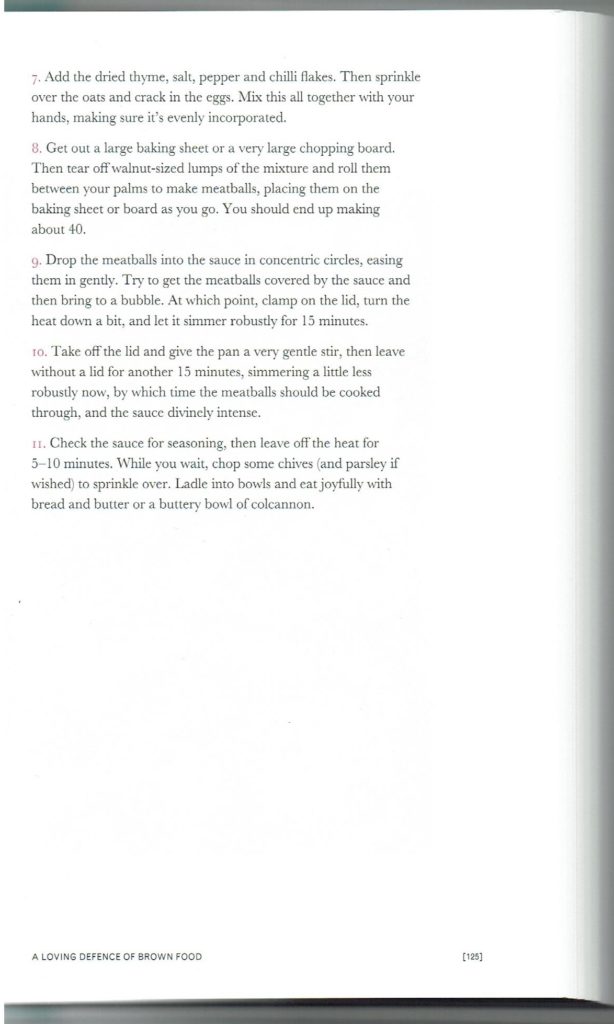

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the domestic practice of blood pudding making began to wane but possibly attributable to growing urbanisation and societal change – especially for women. The practice held out in rural settings longer and is in living memory of older generations, but this typical aspect of rural life begins to disappear rapidly from the mid-20th century. At this time, cookery books authored by Irish women, such as The Cookin’ Woman (Florence Irwin, 1949), My Irish Cookbook (Monica Sheridan, 1965), and A Taste of Ireland (Theodora Fitzgibbon, 1968)[20] are published and include recipes for black puddings. At a time when home-spun recipes were under threat, simultaneously new interest in Irish food and cookery was emerging, and in contrast to men writing about the Irish relationship to blood as food where cooking and recipes were conspicuous by their absence, this time, with women at the helm, the recipe and method become fundamental. The emphasis on recipe transcends the rawness of blood as food into the skilled preparation and cookery of blood pudding, emphasising the influence of women in cementing the traditionality of blood pudding and identifying it as uniquely Irish.

Case Study: Clonakilty Blackpudding[21]

A short history of Clonakilty Blackpudding is contained in Appendix 1. I advise reading this before continuing. A summary follows:

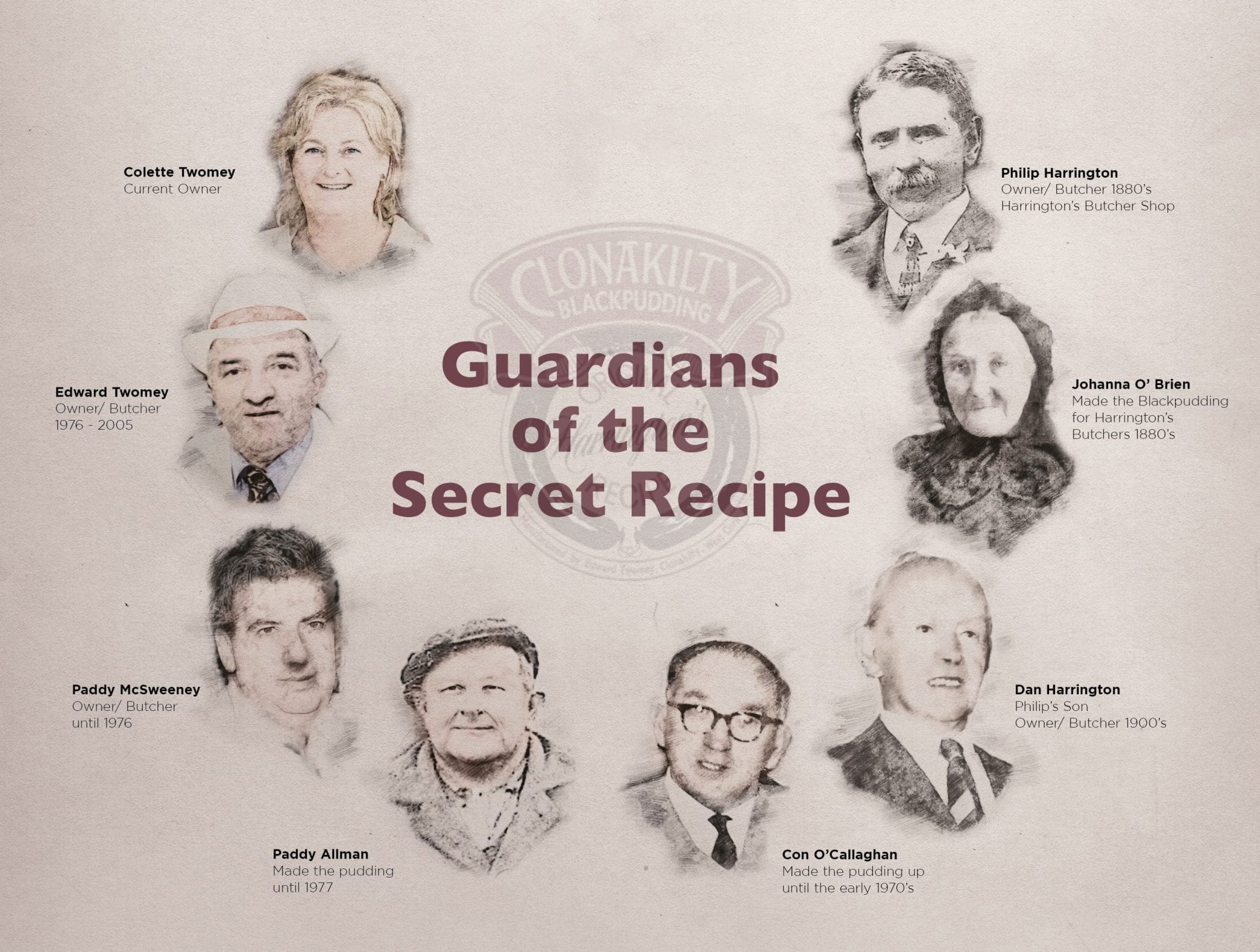

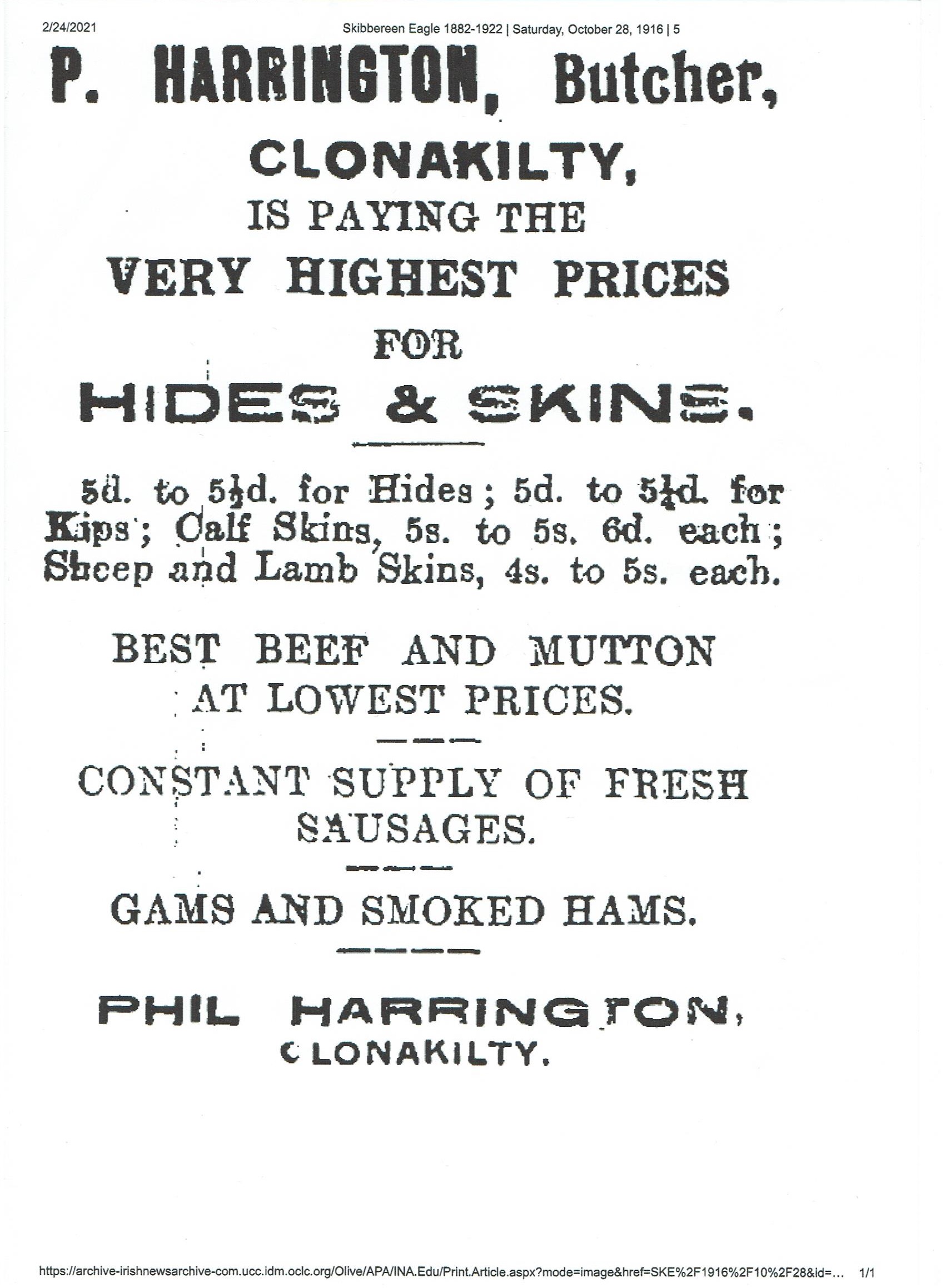

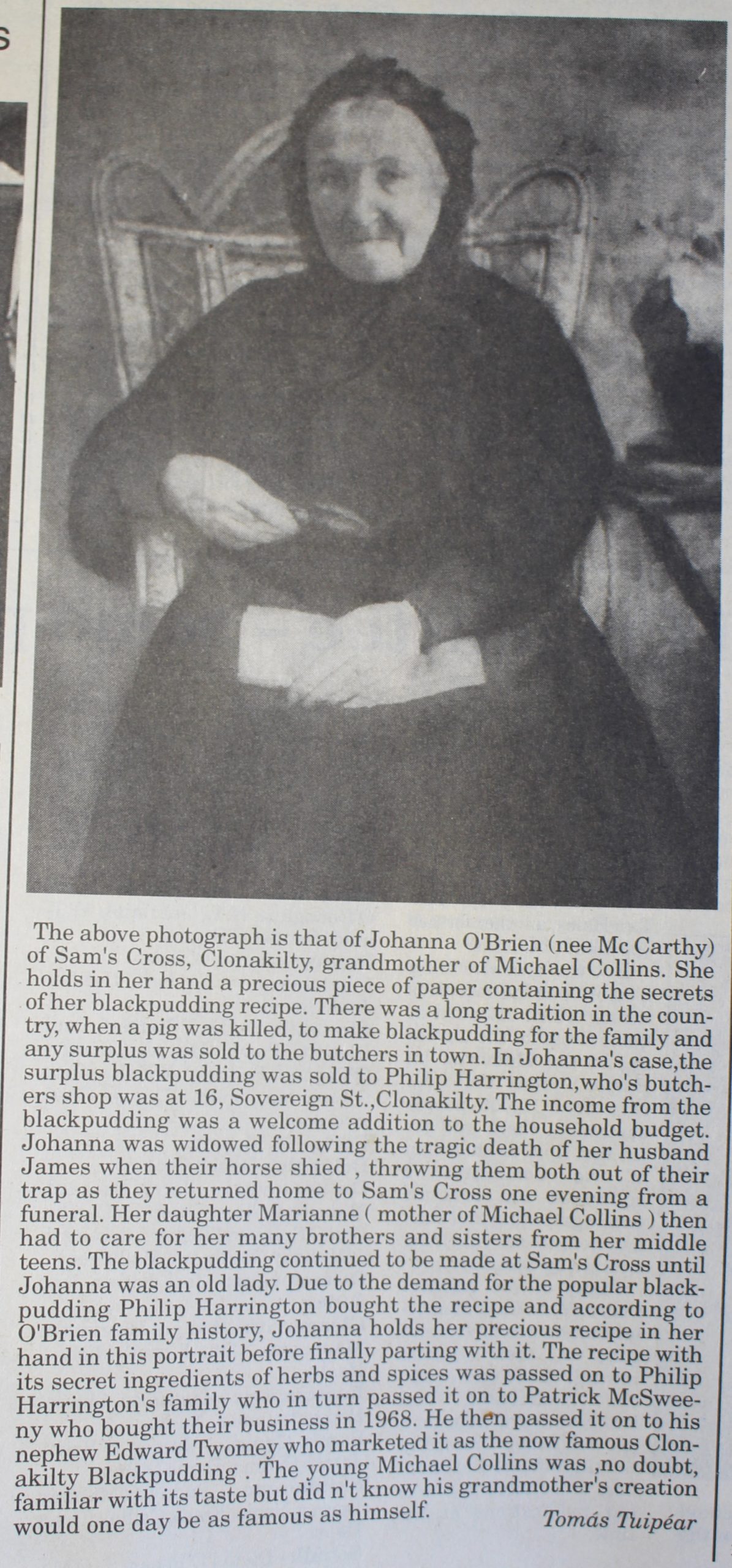

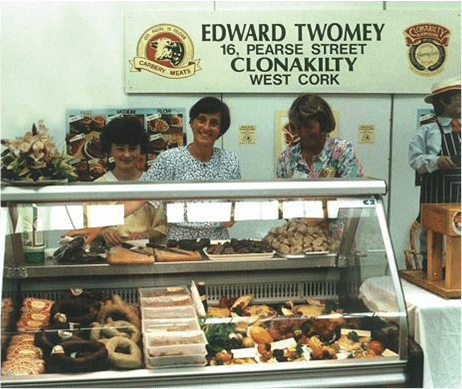

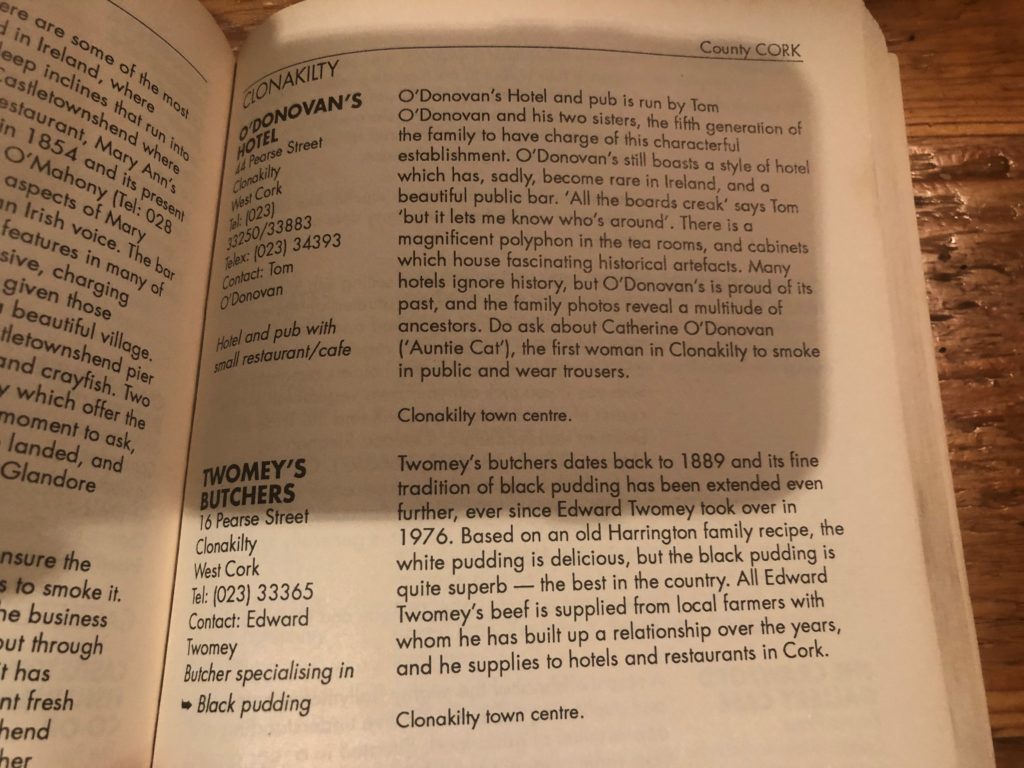

Clonakilty Blackpudding originates from a recipe created by Johanna O’Brien of Sam’s Cross, near Clonakilty, who sold excess puddings to a butcher’s shop owned by Philip Harrington at 16 Sovereign (now Pearse) Street, Clonakilty. In 1889, Johanna sold her recipe to Harrington who continued to make the pudding. Each successive owner of the shop is a custodian of the recipe, and puddings are made to that recipe. In 1976, Edward Twomey purchased the shop and recipe and is credited with popularising this history of Clonakilty Blackpudding, now one of Ireland’s most popular black pudding brands.

Clonakilty Food Co[22] produces a black pudding that engineers the social and cultural history of blood as food in the formation of a unique identity and utilises that identity in marketing and promotion to consumers. Drawing on the history of blood as food in Ireland, the employment of an origin story of a recipe as a marker of authenticity, and the centrality of women to the industry of blood pudding production in the domestic sphere, Clonakilty Blackpudding positions itself as an extant taste of Irish food history. In the intentional creation of a compelling authentic identity since 1976, it could be said Twomey not only reinstated, but improved upon, traditional Irish worldview of blood as food by focusing on the criticality of recipe and ingredients (specifically beef blood and pinhead oatmeal), crediting the role of women and domestic food production, and reversing the deleterious perception of black pudding as peasant food to food of high regard. This is illustrated by food writer John McKenna in a tribute to Edward Twomey after his passing in 2005:

“His passionate belief in Clonakilty pudding convinced everyone of its culinary status. In this regard, the story of Edward Twomey’s Clonakilty Blackpudding is an object lesson in modern food marketing and promotion, and the creation of a luxury food brand.”

McKenna’s comment is key, because it acknowledges that beneath a veneer of authenticity was a pragmatic need to create an identity that conveyed why this pudding was extraordinary:

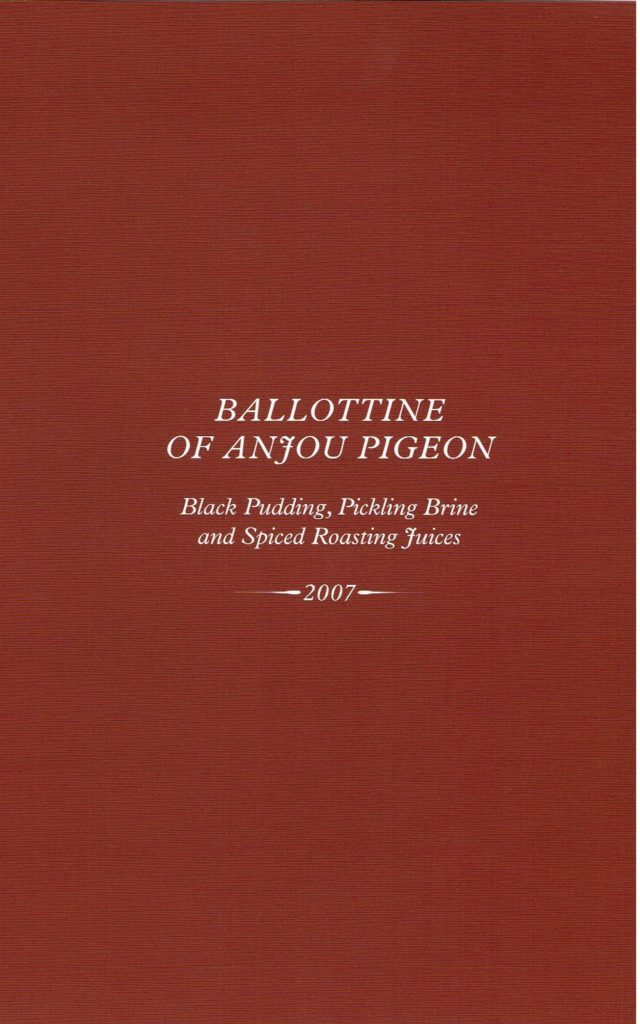

There is no evidence to suggest Twomey was not sincere in his endeavour, however this strategy to create a “menu of prestige”, (R. Sexton, pers. comms., 14th May 2021), took what was notionally valuable about his black pudding and all it represented through the lenses of food, culture, and society – traditional and contemporary, and pronounced Clonakilty Blackpudding as an exceptional food of Ireland, to be considered “perfectly civilised and proper”[23]once more. Such was Twomey’s belief in the goodness and quality of his black pudding, it was presented on the menu of the inaugural Eurotoques dinner, 1989, at Trinity College Dublin in a dish cooked by esteemed Irish chef, Gerry Galvin, who paired “the quotidian black pudding with the princely oyster,” (McKenna, undated).

A Recipe, but not The Recipe

In establishing an identity for Clonakilty Blackpudding, Johanna O’Brien is placed at the beginning of the origin story: the mother of the recipe. We are asked to believe that, from a small rural farmstead in Sam’s Cross 5km from Clonakilty, O’Brien’s black pudding was considered the best such that Harrington paid money to acquire her recipe[24]. Accounts of O’Brien’s extant relatives and local historians accept that her black pudding was likely made from pig’s blood, and that not more than two pigs per year were slaughtered at the farmstead. It is less likely that her puddings were made from cow’s blood, although that is not to say in times when cow’s, or sheep’s blood, was available it could have been mixed to make a blood pudding, much like drisheen. There is no evidence to suggest domestic production was on any significant scale, but outputs of O’Brien’s work on the farm, (butter, eggs, black pudding), represented an important essential source of income, and as such quantities sold to Harrington would vary depending on what was pressing on the household coffers.

It is feasible that, soon after O’Brien sold her black pudding recipe to Harrington, it was adapted and made from beef blood, or potentially a mix of different animal bloods as was to hand as a victualler of beef, lamb, and pork[25]. The label of modern-day Clonakilty Blackpudding states: “Clonakilty Blackpudding. Original Harrington’s recipe. Manufactured by Edward Twomey, Clonakilty, West Cork.”[26] The inclusion of “original Harrington’s recipe” is problematic for the origin story of the recipe: is it O’Brien’s recipe or is it Harrington’s recipe? If O’Brien’s recipe was altered in terms of the blood used to make the pudding is that more, or less, significant than the claim to a secret spice mix? Is the spice mix central to the recipe, or is it blood – the chief ingredient in black pudding?

This is a blending of two origin stories to fit a particular image of homespun black pudding with Harrington, then Twomey, as the clever and adept tradesmen. The narrative of an unchanged recipe with a verifiable lineage is thus created: it is A recipe, but is it The recipe; and does that matter? It matters because, in constructing the origin story for the inherited black pudding recipe, Twomey elevates the role women had in the story of blood as food in Ireland, but he does so in a deliberate manipulation of the past for commercial gain. O’Brien is immortalised, pictured enthroned and clutching her recipe on a piece of paper[27], front and centre symbolising all women who ever made blood pudding before her and since. The significance of this symbology is particularly potent against a backdrop of male dominance in the commercial setting, particularly from the early 20th century onwards, as agricultural and production systems modernised. Women’s personal autonomy, their ability to work and produce income, is threatened: by advances in agricultural practices, and by food production moving from the domestic sphere and centralising, particularly in dairying with the establishment of the Co-Operative movement in 1889.

Towards a new worldview

In an informal interview conducted with food writer, John McKenna[28], on the impact of Twomey’s crusade on black pudding between 1970 and 1980, McKenna said: “The economy was flat, immigration was considerable. It was the time of the Knorr packet soup and dreadful cheeses from co-ops. The Irish were hooked on convenience.” This is a significant indictment on the state of food culture in Ireland in the latter part of the 20th century, one where the Irish worldview of traditional food was entirely altered, and little valued. Into this deeply fissured food culture, where mass-produced packet soup was considered, not necessarily better, but more sophisticated, than consumption of blood as food, enters Twomey brandishing a ring of Clonakilty Blackpudding and eagerly enticing anyone to taste it. “He was the product, and no-one had done that before. He had confidence in something that was really good, and he was the face of it. Eddie wasn’t taking no for an answer, and the fact that he was in West Cork emboldened him to say he was as good as anyone else. He was an irresistible force of nature,” concludes McKenna. Here was a proud Irish man telling everyone from housewives to Michelin-starred chefs how good traditional black pudding was; how flavoursome, healthful, versatile, economical – all the things known before but systematically displaced, forgotten, or lost in favour of modernity.

Twomey approached people who held significant sway in how Irish food was considered and presented. Myrtle Allen, Declan Ryan, Gerry Galvin, and Michael Clifford – chefs at the pinnacle of their careers. Edward Twomey’s Blackpudding was included in the Irish Food Guide (1989), and its author, John McKenna recalls how, in the years between 1989 – 1991, there was a tangible change in Irish food: “People began to respond to Irish food, the change was incredible and there was a sense of excitement by 1991,”[29]: Irish food culture was being reconsidered and revalued and Twomey’s black pudding was key to that.

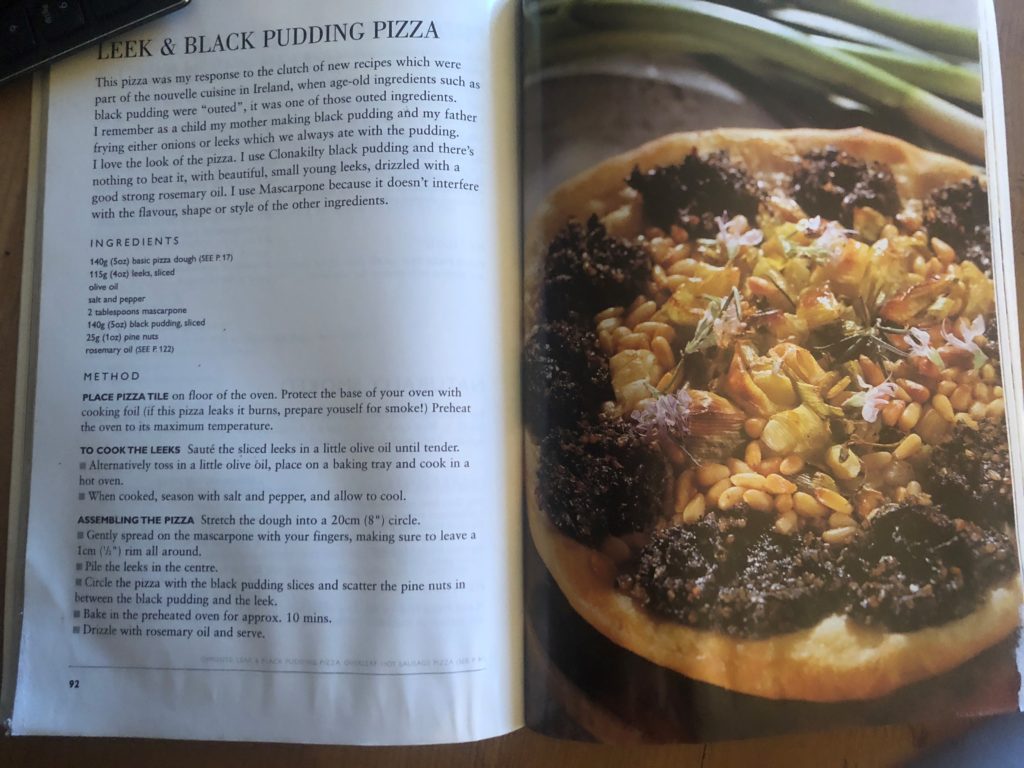

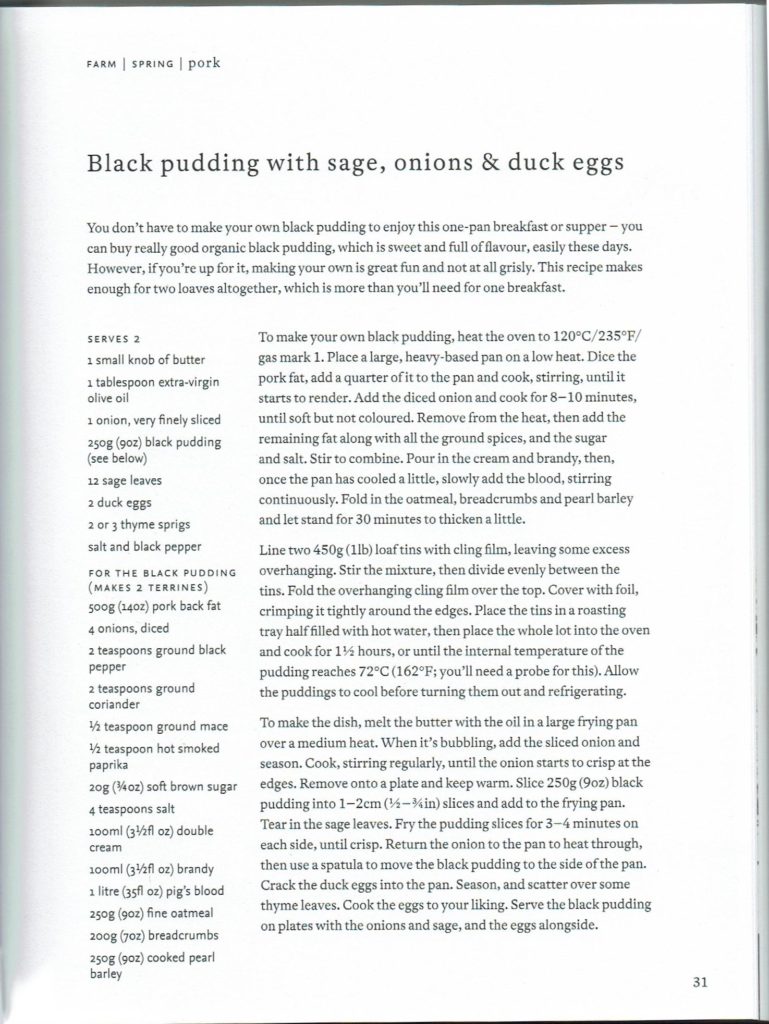

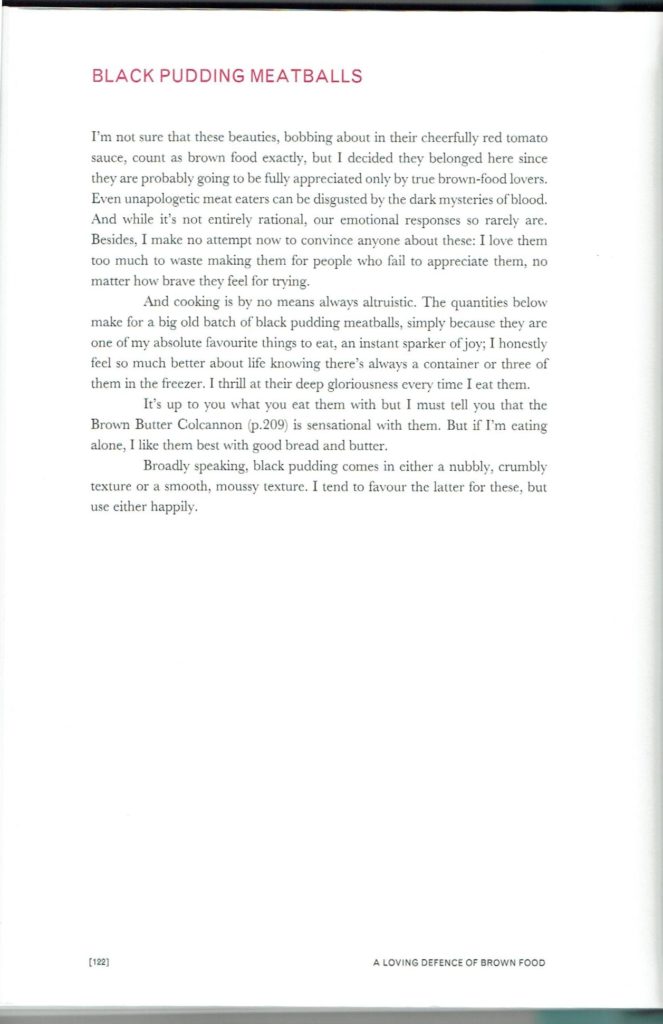

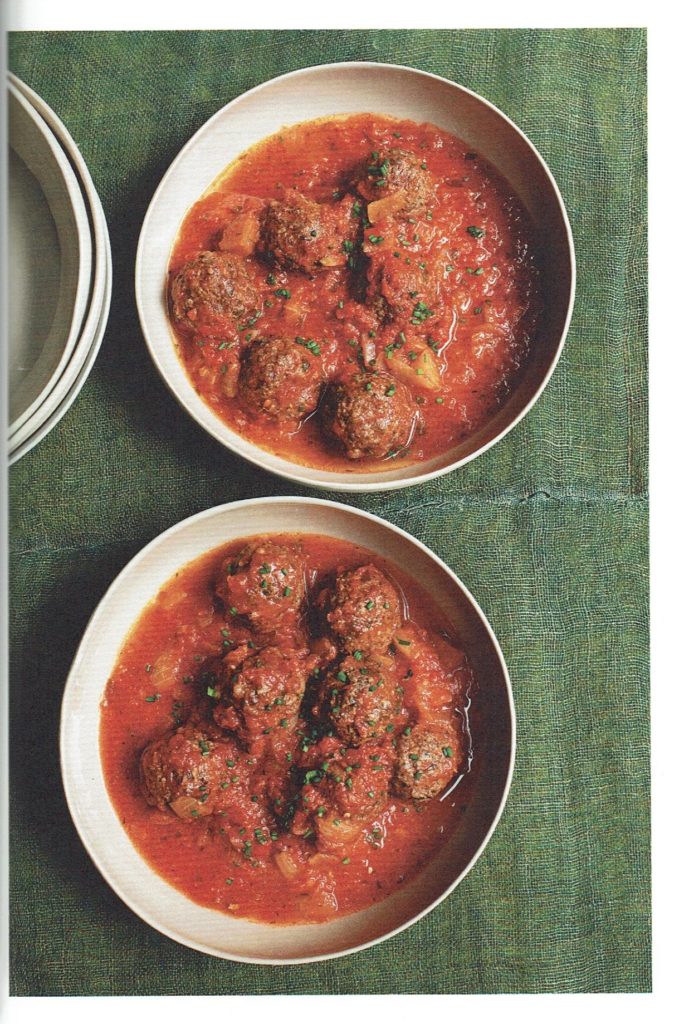

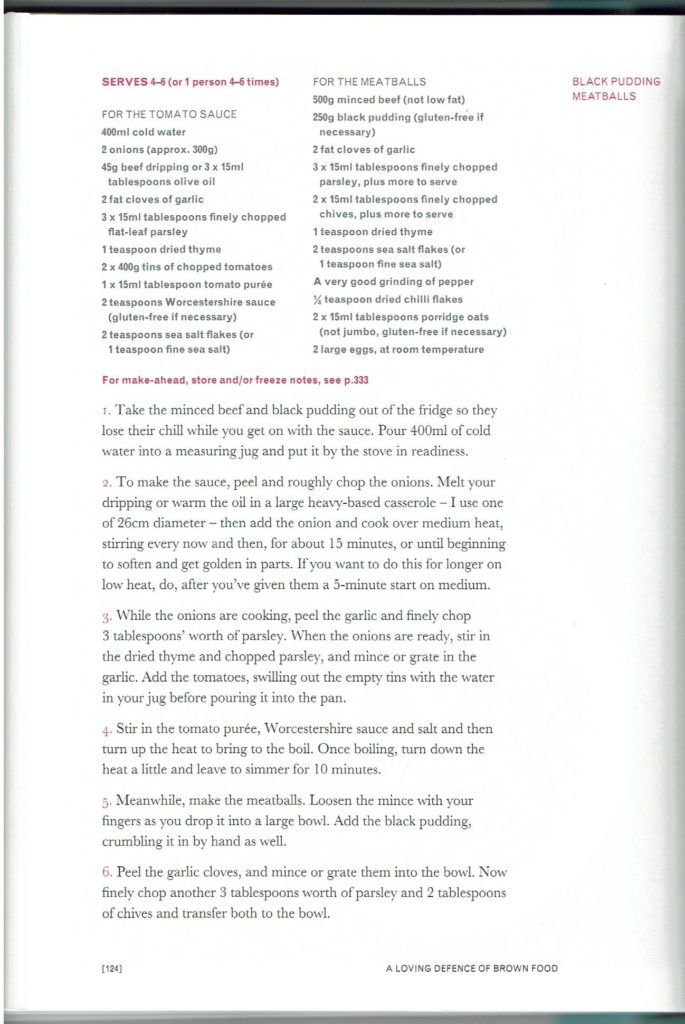

Appendix 4 is a collection of recipes published over the last 80 years, from methods for making black pudding and drisheen at home, to ‘cheffy’ recipes using black pudding in sauces, stuffing’s, or pizza toppings. Contemporary recipes are a hybrid of homespun recipes for making black pudding and drisheen (McMahon, 2019) to British author Nigella Lawson’s recipe for Black Pudding Meatballs (2020) who comments in the headnote: “Even unapologetic meat eaters can be disgusted by the dark mysteries of blood,” a remnant of the old ‘other’ thought and language of blood as food. Perhaps it is fitting to return to the writings of Lucas (1989) who says, “All things considered, it would seem that the custom [of blood drawn from live cattle] should be construed as an ancient and normal component of Irish dietary habits […].”[30] I am not advocating the return of live bleeding animals, but I would advocate for better consideration of the social and cultural identifiers of blood as food in Ireland.

CONCLUSIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The dearth in primary material in my area of research does not correlate with a dearth of information available in the wider sense. As noted in the Methodology with regards to the informal interviews conducted, there is a dense body of living memory accounts to be mined for information. Most is held within the memory of an older generation of people and the last to remember blood pudding making in the domestic environment. If it is not captured, this knowledge may rapidly disappear from living memory within the next one or two decades. As the National Folklore Collection shows, there is little detail on blood as food or domestic black pudding making in the accounts collected by the Folklore Commission. In my analysis, I argue that a scarcity of such information could be attributed to parallel changes in Irish food culture and society in general; but it could also be indicative of who is asking questions of informants. The all-male worldview of Folklore collectors may have had an influence in what is considered important, valuable, or worthwhile collecting. There is an opportunity to enquire specifically on blood as food and blood pudding making; and should accounts repeat themes or activities across Ireland, there is still value is collecting to analyse for variances. For instance: why are some blood puddings in casings, but others resemble a cake?

I would recommend more research into recipes. In conjunction with the process of making puddings, recipes locate women central in the blood as food tradition. From accounts analysed in my research, each home had its own recipe known only to the woman of the house and rarely written down. Depending on time of year an animal was slaughtered, seasonal variations in recipes could affect inclusion of ingredients into puddings: grains, flavourings – particularly wild herbs, and spices. Such information would provide insight into what other produce was available, whether it was procured or grown, and, in the case of wild herbs, could be a key identifier of place, season, method, and maker. The individual nature of blood pudding recipes shows up in the commercial sphere where butcher’s guard their recipe. In the case study of Clonakilty Blackpudding, I demonstrate how this secret recipe in central in their origin story and marketing strategy. Another local butcher, three generations making black pudding in Clonakilty, also guards his recipe identified as handed down from his great grandfather, but likely to have originated with his great-great grandmother. The commercially sensitive nature of blood pudding recipes originates with the women who made puddings at home and as such are signatures of identity yet are disconnected from the narrative.

Word Count: 7150

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, D., (2009) Forgotten Skills of Cooking, Great Britain, Kyle Books.

Binchy, D. A., ed., (1978) Corpus iuris hibernici, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

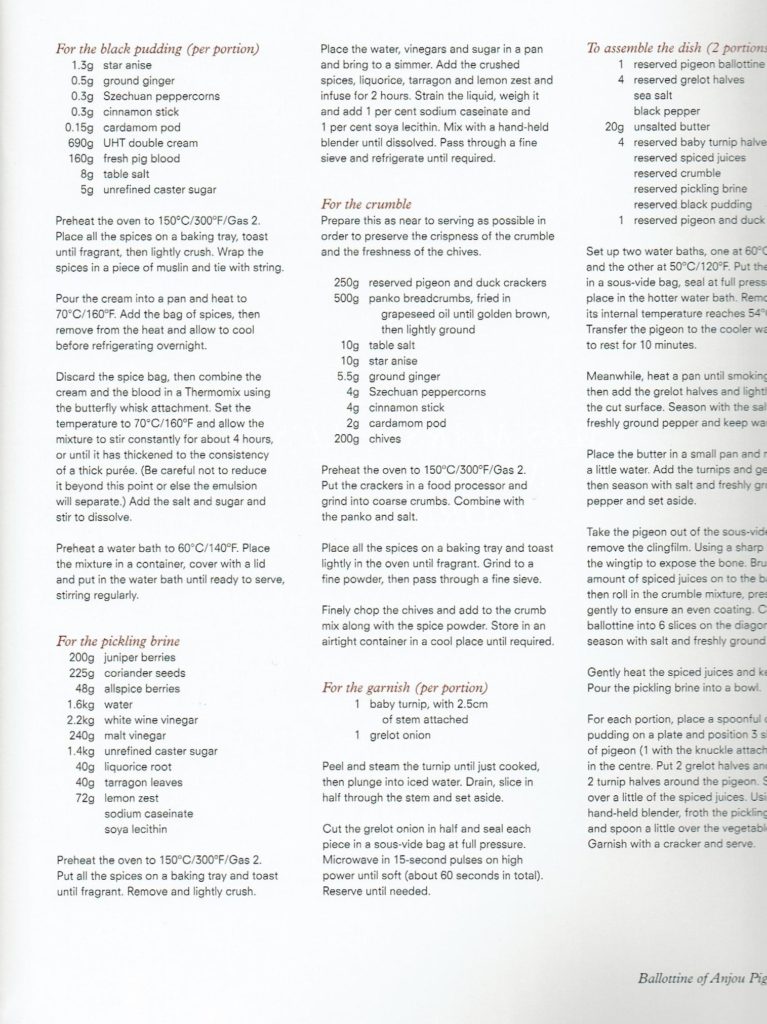

Blumenthal, H., (2009) The Fat Duck Cookbook, London, Bloomsbury.

Collingham, L., (2017) The Hungry Empire, How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World, London, The Bodley Head, (Vintage Publishing/Penguin Random House UK).

Clonakilty Food Co. (2019) The Black and White Cookbook, Ireland, self-published.

Clonakilty Food Co. (2020) The History of Clonakilty Food Co. [online], available: https://www.clonakiltyblackpudding.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Full-history-Document-updated.pdf

Davidson, A., (1999) The Oxford Companion to Food, Oxford University Press.

Edie, C. A., (1970) ‘The Irish Cattle Bills: A Study in Restoration Politics’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 60, Part 2, pp 1- 66, [online] https://www.jstor.org/stable/1006099?seq=1 [accessed 14th January 2021].

Fitzgibbon, T., (1968) A Taste of Ireland, London, Pan Books (1st edn, 1970).

Freeman’s Journal Sydney NSW, (1917) ‘Obituary Mrs Johanna O’Brien, Clonakilty’ 8th March 1917, p. 20.

Hamilton, H. D., (2003) The Cries of Dublin &c, Drawn from the Life by Hugh Douglas Hamilton 1760, Dublin, Irish Georgian Society.

Hickey, M., (2018) Ireland’s Green Larder, London, Unbound.

Irwin, F., (1949) The Cookin’ Woman, Edinburgh, Oliver and Boyd.

Lawson, N., (2020) Cook, eat, repeat London, Chatto & Windus.

Lucas, A. T., (1989) Cattle in Ancient Ireland, Kilkenny, Boethius Press.

Lucas, A. T., (1989) ‘Blood as Food’ in Cattle in Ancient Ireland, 1st edn, Kilkenny, Boethius Press.

Meyer, K., (1892) Aislinge Mac Con Glinne – The Vision of MacGonglinne A Middle Irish Wonder Tale, London, David Nutt.

McCarthy, C., (2019) ‘Johanna McCarthy (Gaibhdeach) O’Brien (Grandmother of General Michael Collins)’ Cork Rebel Way – The Road to Irish Freedom, Vol. 1, pp 60-61. [online], available: http://www.michaelcollinscentre.com/corkrebelway.pdf

McCarthy, K., (2016) The Little Book of Cork, Cheltenham, The History Press.

McKenna, J., McKenna, S., (1989) The Irish Food Guide, Dun Laoghaire, Anna Livia Press Ltd.

McKenna, J., (undated) Gerry Galvin (Mega Bites Blog Post), [online] https://www.guides.ie/blog/gerry-galvin [accessed 24th February 2021].

McKenna, J., (2005) ‘Edward Twomey – John McKenna on the man who brought Clonakilty Black Pudding into the world’, Sunday Independent, 4th December 2005.

McMahon, J., (2020) The Irish Cook Book, London, Phaidon.

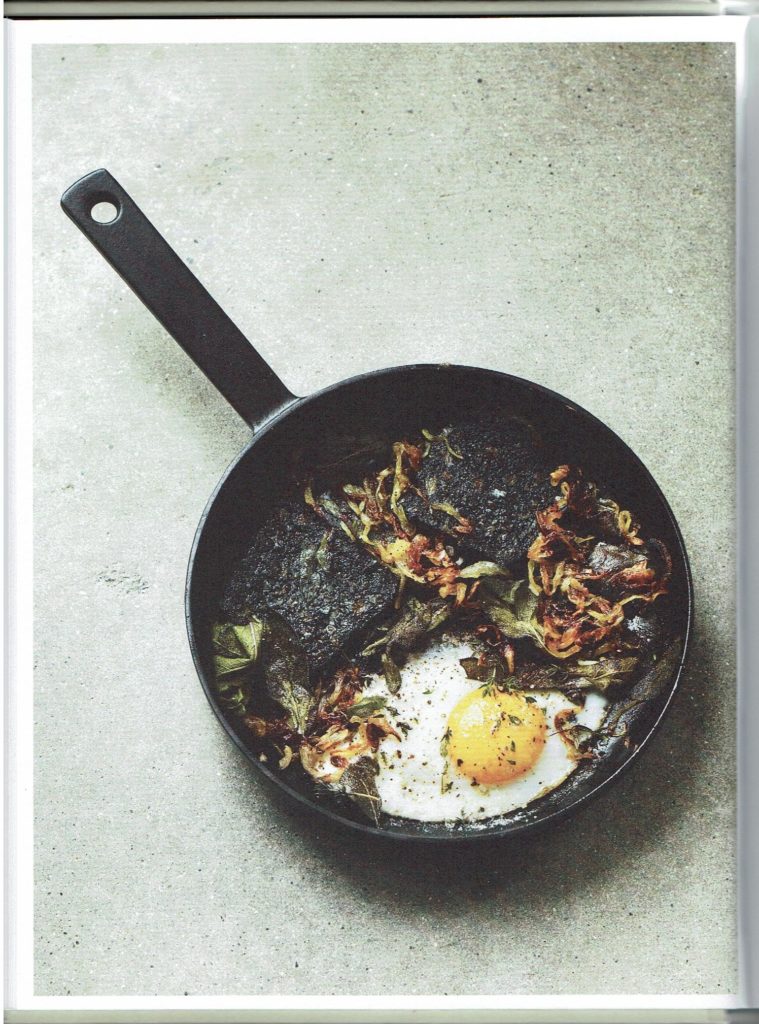

Meller, G., (2016) Gather, London, Quadrille.

Morton, H. V., (1930) In Search of Ireland, London, Methuen & Co Ltd.

Murray, A. E., (1907) ‘A History of the Commercial and Financial Relations between England and Ireland from the Period of the Restoration’, Studies in Economics and Political Science, No. 13, pp. 1-486. [online] https://celt.ucc.ie//published/E900040/index.html [accessed 14th January 2021].

O’Shea, B., (1997) Pizza Defined, Durrus, Estragon Press.

Rankin, P., Rankin, J., (2005) New Irish Cookery, London, BBC Books.

Sexton, R., (1995) ‘“I’d ate it like chocolate”: the disappearing offal food traditions of Cork City’, in Harlan Walker (ed.), Disappearing foods: proceedings of the Oxford symposium on food and cookery, Devon, Prospect Books, pp. 172–88.

Sexton, R., (1998) A Little History of Irish Food, London, Kyle Cathie Limited.

Sexton, R., (2016) ‘Food and culinary cultures in pre-Famine Ireland’ in Fitzpatrick, E., Kelly, J., eds. Food and Drink in Ireland, 1st edn, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy.

Sexton, R., (2018) ‘Elite Women and their recipe books: the case of Dorothy Parsons and her Booke of Choyce Receipts all written down wth her owne hand in 1666’, in Dooley, T., O’Riordan, M., Ridgway, C., Women and the County House in Ireland and Britain, 1st edn, Dublin, Four Courts Press.

Sheridan, M., (1965) My Irish Cookbook, London, Frederick Muller Ltd.

Taylor, A (2015) The Women, O’Brien Press.

Tuipéar, T., (2002) ‘Johanna O’Brien’, West Cork People Commemorative Edition, 24th August 2002.

Wickham, A., (2013) Women Speak, Life for Clonakilty Women in the 1900’s Volume 1, selfpublishbooks.ie.

IMAGE REFERENCES

Appendix 1

Image 1 from the Clonakilty Blackpudding Company website illustrating the past owners of the shop, holders of the recipe and makers of the blackpudding. www.clonakiltyblackpudding.ie

Appendix 2

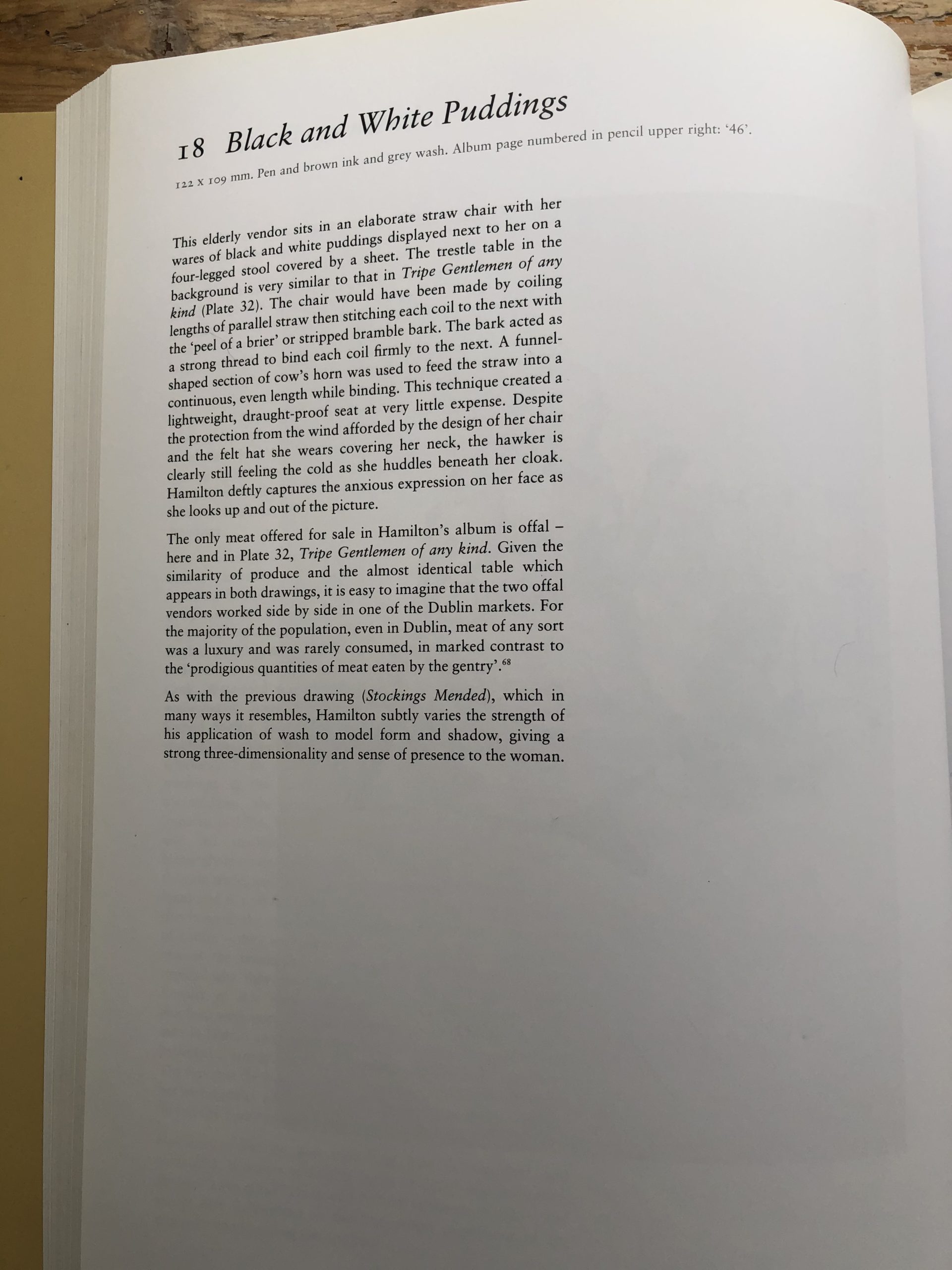

Image 2.1a Reproduction of Plate 18 ‘Black and White Puddings’ Hamilton, H. D., (2003) The Cries of Dublin &c, Drawn from the Life by Hugh Douglas Hamilton 1760, Dublin, Irish Georgian Society.

Image 2.1b Descriptive Text relating to Plate 18 ‘Black and White Puddings’ Hamilton, H. D., (2003) The Cries of Dublin &c, Drawn from the Life by Hugh Douglas Hamilton 1760, Dublin, Irish Georgian Society.

Image 2.2 Advertisement in the Skibbereen Eagle Newspaper, 28th October 1916.

Image 2.3 Official brand logo of Clonakilty Blackpudding. www.clonakiltyblackpudding.ie

Image 2.4 Copy of a photograph of Johanna O’Brien holding the black pudding recipe. Tuipéar, T., (2002) ‘Johanna O’Brien’, West Cork People Commemorative Edition, 24th August 2002.

Image 2.5 Clonakilty Blackpudding at the Cork Show, 1988.

APPENDIX 1 – A SHORT HISTORY OF CLONAKILTY BLACKPUDDING

In 1976, Edward (Eddie) Twomey purchased a butcher’s shop on 16 Pearse Street, Clonakilty. It came with a recipe for black pudding that had been made in the same way at the same location by all the butcher’s that had come before him since 1889[31] when the recipe was acquired by Philip Harrington from Johanna O’Brien, an elderly lady who had been widowed young, on the advent of her retirement. Johanna O’Brien made her black pudding on the farmstead at Sam’s Cross approximately 5km from Clonakilty. After becoming widowed, she tended the farmstead with her eight children, and, along with any surplus butter or eggs, sold black pudding to Harrington’s[32] providing essential income to the farm. A photograph of Johanna O’Brien25, said to be taken on the day she sold her recipe for black pudding to Harrington, shows her seated in black formal dress and bonnet typical of West Cork at the time, holding a pair of glasses in one hand and in the other, a piece of paper purported to be the recipe. When Twomey purchased the butcher’s shop, Paddy Allman, employed by the previous owner, made black pudding to this recipe but passed away suddenly in 1977[33] leaving no other to continue making the pudding. Considering it old-fashioned and too time consuming to make, Twomey stopped producing the pudding, but soon after trade across the butcher counter dipped, and he realised his customers came for the pudding first and foremost and stayed for the meat. Production of Clonakilty Blackpudding recommenced, and Twomey with his wife Colette, (CEO since Twomey’s death in 2005), took their black pudding on a county-wide, then country-wide, roadshow cooking up the pudding and giving it to people to taste, even appearing on an episode of The Late, Late Show in 1989 with Gay Byrne – everyone in audience was gifted a hamper of Clonakilty Blackpudding. Twomey extolled the virtues of his flavoursome pudding, telling people about the secret spice mix from Johanna O’Brien’s original recipe, that it was uncommonly made with beef blood not pig’s blood, and, emboldened from West Cork, (the home of highly regarded artisan food producers at that time), pronounced Clonakilty Blackpudding as one of Ireland’s finest foods produced and savoured. Such was the power of Twomey’s belief in the goodness and quality of his black pudding, it found itself on the menu of the inaugural Eurotoques dinner, 1989, at Trinity College Dublin in a dish cooked by esteemed Irish chef, Gerry Galvin, pairing “the quotidian black pudding with the princely oyster,”[34] and has been gracing menus ever since. In 2017, a new state-of-the-art production facility and headquarters of Clonakilty Food Co was officially opened. The facility cost €7 million to build[35]; a Visitor’s Experience opened in 2020, and in that same year 924,389kg of Clonakilty Blackpudding[36] rolled off the production line.

APPENDIX 2 – IMAGES

| Appendix 1 | Description |

| Image 1 “Guardians of the Secret Recipe” From the Clonakilty Blackpudding website illustrating the past owners of the shop, holders of the recipe and makers of the blackpudding. www.clonakiltyblackpudding.ie |

| Appendix 2 | Description |

| Images 2.1a and 2.1b 2.1a reproduction of the Plate 18 ‘Black and White Puddings’ Hamilton, H.D., (2003) The Cries of Dublin &c, Drawn from the Life by Hugh Douglas Hamilton 1760, Dublin, Irish Georgian Society. |

| Image 2.2 Advertisement placed by Philip Harrington, butcher at 16 Sovereign (now Pearse) Street, in the Skibbereen Eagle Newspaper, 28th October 1916. The advertisement ran once a month for three months. |

| Image 2.3 Official brand logo of Clonakilty Blackpudding. www.clonakiltyblackpudding.ie |

| Image 2.4 Copy of a photograph of Johanna O’Brien purporting to hold the recipe for her black pudding in her left hand, a pair of spectacles in her right hand. This image is said to have been taken on the morning O’Brien handed over her recipe to Philip Harrington and was felt to be an auspicious occasion. This image was hanging on the wall of the hallway of Jimmy O’Brien, Johanna’s grandson, on the day Edward Twomey came to visit. |

| Image 2.5 Clonakilty Blackpudding at the Cork Show in the summer of 1988. Note how samples of the pudding in natural casing have been sliced and cooked ready for handing out and tasting. |

APPENDIX 3 – PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS (INFORMAL INTERVIEWS)

| Personal Account 1 Recorded 1st March 2021 Transcribed 21st May 2021 Phyllis Ryan, aged 71, was born and raised on a small farm in Feenagh, Co Limerick, (see also Fenagh). In this informal interview, Phyllis recalls the day the pig was slaughtered at the family farm, the preparation and preservation activities for the meat, making black pudding, communality, eating fresh meat, sights and sounds of the day. Full permission was given to record the conversation in an audio file, and for her recollections to be transcribed and included in the research project. (Disclosure: Phyllis Ryan is mother-in-law to Kate Ryan, author of the research project). |

There’s just one time I remember, and actually I was talking to Betty (my sister) the other night, and thought, well now, she must have been there for some of it, and she might remember more than me, so, it’s so funny because there’s a friend of hers then from Mitchelstown and she’s always in contact with her, she nursed with her, she has all the stories, so she was talking to her and getting more information from her and they had a great laugh over it.

This one time that sticks out in my mind, maybe I was a little bit older and happened to be there and it stuck with me more, because they killed a pig every year at home, but I suppose we were just as kids running around and not really taking any notice of it. Maybe they didn’t let us see it happen, you know? I don’t know, but this one time I can remember alright now, where it was actually a butcher that came, and he killed the pig. It was our own pig, and it was done in the piggery after it had been cleaned out and all the other pigs had been sold and this one was kept to be killed, and then it was all cleaned out and the pig was hung up there. It wasn’t a very nice experience I must say when they killed the pig, they cut his throat, and then they had a bucket underneath him to collect the blood. The men were did the killing of the pig, after they had killed the pig and he was hanging for a little while, I can’t remember that, but then they had to scald him with hot water, and shaved the pig, and then after that, I can remember them having a table where they put him on and cut it all up into sections, and he was put into salt barrels and salted and kept, the same barrels used over and over and new salt added. The only thing that was brought into the house was the blood for the black pudding and the pork steaks. Like, when they’d bring in the pork steak then and they’d cut it into pieces and that would be given out to the local neighbours, and when my mother would make the black pudding she’d give some black pudding to the neighbours as well. She didn’t sell any black pudding, but my mother might have given some to the butcher who killed the pig to take home, but it was all given out to the neighbours, and then when they killed their pigs, they’d do the same, give out some pork steak and black pudding.

I can actually remember, like, it was barley and breadcrumbs and onion that was put in with the blood and I can remember stirring it. It was all stirred first with all of that and mixed, and then they’d clean the intestines, all the women did that work. But then they’d fill all the intestines with the mixture, then when they’d be all tied up, you know, and done in rings, they’d be put into a big pot and boiled.

An awful lot of work went into making it, and like, they’d start at early in the morning, the pig would be killed at about 6 or 7 o’clock in the morning, and by the time they’d have it all cut up and everything, they’d have to keep some pieces out to use as fresh pork, but all the rest of it then was put in the barrels, but by the time – they had to rub salt into all of that and it had to be layered inside of the barrel so many pieces, and then more salt on top of it – it was a long process. But then they had meat then for most of the year. There’d be just my mother and father, maybe Den and Mike and Myself, Pat probably, but Betty, Peg, Seamus and Mary were all left home. It was mainly my mother that did all that work, and then there might be two or three of us there to help. I suppose I was about 8 or 9 years old, that age, you know.

I doubt the pudding was ate on the day it was made, I think it was left. Actually, what I can remember is when however long it went onto boil, when she’d take it out of that pot, I can remember, Betty was laughing at me, the sweeping brush and she’d put the sweeping brush between two chairs, and she’d hang all the rings along the sweeping brush – the handle of it – to let them dry out. Betty was killing herself laughing when I was telling her that! We used to have a couple of brushes going between the two chairs and all the pudding hanging off it. Probably 12 or 16 maybe, I’m thinking of the size of the brush handle now, and they were spaced out on the…yeah, I suppose about 12 maybe.

We wouldn’t have that many of them then because they’d be a ring of pudding given to most of the houses around to the neighbours, you know. All the neighbours that time, the farmers now, when they’d have their new potatoes, they’d always give out a small little bag or bucket of new potatoes to a certain amount of their near neighbours, so everything was kind of shared out, you know, and as I say, like, if some of them wouldn’t be farmers, if they had chickens or geese or that so you might get a chicken from another neighbour. There was a lot of that.

The pudding was just fried, I don’t remember her doing anything else with them, fried in lard, sliced off the ring. Sometimes they were done as dinner, especially for the first few days with some of the pork steak and that. That would be fried as well. That taste of fresh, unsalted meat, absolutely everybody was mad about that, that was like having fillet steak now, a real treat, and you wouldn’t have that much of it, you see, by the time you had given a little bit to everybody, so what we had for ourselves wouldn’t be much of it.

It was such a busy day because there was so much going on, I’m sure just to take a long time, as I say, it was most of the day making the pudding. I can remember stirring it for ages and ages to combine everything into it. We had an old-fashioned metal range, we burned anything on it for fuel.

I wouldn’t have thought to mention it, only that Jason had mentioned what you were doing, and I said I remembered that, but other than that, you know, I’d never think of talking about it.

The farm is in the family still, and part of the piggery is still there – one half of the garage now! We never as kids stayed around when the pig was being killed, we used to run away into the fields and climb trees and stay there because we hated the noise of the pig. It wasn’t a very nice thing, but I supposed as kids we forgot about it pretty quick, and it was so busy then, the day, and so much going on, that you were dying to get the pork steak because it was a great novelty, of course, because you wouldn’t have any fresh meat at such, going back.

It’s a shame through the generations that people didn’t pass these things on or talk about them, you know, it was just part of their lifestyle and they took it for granted and didn’t bother, and as other generations came along, they had no interest in it.

| Personal Account 2 Recorded 26th February 2021 Transcribed 21st May 2021 John McKenna is an Irish food writer and co-founder of the Bridgestone (now McKenna’s) Guides to food and drink in Ireland. The first edition published in 1989 included an entry for “Twomey’s Butchers” and McKenna became friendly with Edward Twomey as their paths repeatedly crossed professionally. McKenna wrote about the first Eurotoques dinner which he credits as an important food culture moment for Clonakilty Blackpudding; and wrote a tribute to Edward Twomey who passed away suddenly in 2005. Full permission was given to record the conversation in an audio file, and for his recollections to be transcribed and included in the research project. (Disclosure: John McKenna is a Member of the Irish Food Writer’s Guild. Kate Ryan, author of the research project, is the current Secretary of the Irish Food Writer’s Guild). |

I would have come down to Dublin from Northern Ireland, although I would have been frequent visitor to the republic because my mother is from Carlow, in 1977 a student and I’ve been living in the Republic ever since. The simple fact of the matter is: when Eddie took over the shop in the 1970’s there was really little or nothing happening in what we might call creative Irish cooking either in terms of artisanship or in terms of restaurant cooking – quite genuinely. The economy was completely flat, emigration was still very, very considerable, everybody who could get a J1 visa got one to go off to the States, everybody else went to London. During the 70’s really there was really, as I understand it, little or no artisanship in Ireland, it was the time of Knorr packet soups and the dreadful cheeses in the little box from the co-ops. Of course, probably in private houses, there would have been some interesting cooking – you did have some people doing interesting stuff, Gerry Galvin in Kinsale, Myrtle obviously in Ballymaloe; but as an overall picture when Eddie took over was a time when the Irish were getting hooked on convenience – which is to say: nobody made oxtail soup anymore but everybody drank or ate oxtail soup because Knorr made a packet which made 1.5 pints.

Also, if you went to eat in places, the menu would say “homemade vegetable soup” but what it was a dehydrated packet into which they added boiling water – quite literally and served. So, when Eddie took over in the 70’s there was little or nothing going on really. It was later on that Veronica Steele would begin to make Milleens [cheese], thereby precipitating Gubbeen, thereby precipitating Durrus and the three cheeses on the three peninsulas. You probably had a small number of people coming in from Europe, particularly Holland, so you would have had people like the Wilhems’s making Coolea, there were a number of English hippies, these people went to Leitrim because you could buy a homestead for nothing. The locals would laugh at them because they would say: even the donkeys can’t live there. So apart from those blow-ins, the story of Ireland in the 70’s when Eddie bought the shop is really one of exodus really. There wasn’t anything going on, which is a further kind of tribute to what he achieved.

I first met Eddie in 1989, and what you began to become conscious of when you began to know the group of West Cork artisans then, (the Fergusons, Jeffa Gill, Sally Barnes), Eddie was a constant presence at all of the shows. They would always be doing little agricultural shows, anything to give people a taste of something; and a lot of time people wouldn’t want a taste of Gubbeen, you know, all: Oh, no, I don’t eat that, you see, that common place kind of thing. And one of the things that Eddie did, not by really like telling people that black pudding was made with blood, but just by handing it out for free, and just by getting on the road and going to down to Ballymaloe and going everywhere saying, you have to put this on the menu, this is the real thing.

I suppose there were two things he did which were extremely unusual, and we did our first book in 1989, and I think that was when I first met him in the March of ’89; and what Eddie did was, he identified himself with his food – that was the major breakthrough. Like, if I get somebody over the course of years doing consultancy or something asking me well, what do I say about my product? I say, you’re the product; you’re the story and you are the product, because you’re the maker. But Eddie did a second thing as well as identifying himself with the product, which nobody had done before, he said: this product was a historical artefact in Ireland’s food culture – it has a story, it has an importance, and I am the continuum of this tradition. And remember, he’s doing this at the time everyone is having packets of Knorr soup, and thinks that cheese comes wrapped in a little box with a little girl on the cover, or else it’s a Dairylea Single.

Those two things: his confidence in the fact that he had something really good, and secondly the fact that he was the face of it, was really kinda extraordinary, you know. And I think that he was a little bit fortunate as well that people like Myrtle, people like Declan Ryan, these people are interested in that, they wanted that. Myrtle and Declan, both are Francophiles, what they wanted was a local thing, and suddenly here’s this local food from Clonakilty, here’s this Milleens cheese from Beara; and they wanted that which was a change from the other restaurants who didn’t want it. If you in those days, the early days of Restaurant Patrick Gibault in Dublin, there was no evidence that you were really in Ireland – you could have been in Tokyo. There was no interest there in having anything that was coming from Ireland, oysters, maybe, possibly lobster, but that was the height of it.

Eddie had a different kind of orientation, and again, everybody needs a champion, and Eddie not only found a champion in Myrtle and Declan, but when Gerry Galvin at the first Eurotoques big dinner in the dining room of Trinity College, (and it was a big night), and Gerry’s starter was black pudding with oysters and an onion and apple confit, the recipe he gives in his cookery book, and everybody went “F*ck me,” you know, what is this? This is something you eat for breakfast, and this was Gerry’s genius you see, Gerry re-contextualised what black pudding was, because he could see the significance of it – other people had it placed: eaten for breakfast at weekends; Gerry’s brilliance was he could recontextualise it, and that is what he did at that dinner.

I’ve often said, Myrtle opening Ballymaloe in 1964 is the big bang, but that dish at that dinner was actually one of the big bangs because it said not just to Eddie Twomey but to everyone that was there: this is not just a peasant food, this is not something you eat when you have a hangover on Sunday morning – this is serious. And nobody had really done that before. There was a little bit of attention for Milleens and Gubbeen and so on, Giana and Veronica were good at selling their product; but it took until that time for Eddie’s persistence to really pay off, and then suddenly for example, the London Independent which was a very good newspaper in those days in the early 90’s, had a correspondent: Alan ?, I didn’t really know him well, but he was their Ireland correspondent, and he wrote a big story on Eddie and they sent a snapper over, which is what used to happen in those days, to Clonakilty to take a picture of Eddie and the pudding, and that wasn’t really happening with any other Irish foods, you know? Even though it was a little bit kinda “oh my god, look at this strange thing made of blood,” but of course Eddie didn’t give a sh*t – there he was, actually real seriously quality media which the Independent was for a number of years, and that was really the thing.

But you really have to give Eddie the credit for that period in the 70’s and 80’s there is very very little happening. At the end of the 80’s, suddenly you’ve got Paul Rankin and Rosscoff in Belfast; the Ryan’s in Arbutus, you’ve a few other people happening, but its worth noting for example that Galway as a city to eat was terrible, and the best place to eat in Galway was Gerry Galvin’s restaurant which was in Moycullen which isn’t even in Galway! Kinsale was totally over-rated – Ireland’s ‘Gourmet Capital’, and that is where I first met Eddie at the very food Irish Food Symposium in 1989. Joe Walshe was Minister for agriculture who organised it (a Cork man), it was in Kinsale because they had the bedrooms and they brought in a number of journalists from England, there was another on in 1991; but Eddie wasn’t a player in that. I met him because a bunch of us, Eddie, Otto Kuntz who was then a protégé of Gerry Galvin and was cooking in Dunworley, had a sort of informal meeting and that was when we first came down to Clonakilty and met Eddie. But Eddie just had that persistence – he was a bulldog, he believed he had something, he believed he had a story, he represented it himself which was very brave because there was nothing slick about Eddie!, far from it, but he was an irresistible force of nature, and single handedly he changed the perception of black pudding, but not on his own: he needed Gerry Galvin to do it; he needed Myrtle Allen to do it. But Gerry’s dish at that Eurotoques was the big bang when this food is suddenly recontextualised, is placed in a grand scenario – the dining hall at Trinity College, and then it was just unstoppable.

Everybody began creating recipes using it, and not just throwing it in the frying pan – twice baked black pudding souffle is another of Gerry Galvin’s signature dishes. People began to respond to the ingredient, and you see, that was when you begin to get a sense of excitement in Irish food because, we did our first book in 1989, our first Bridgestone Guide in 1991, and the difference in the space of two years is absolutely startling. You suddenly have in Roscoff, in Belfast where there was very little good food, you have the greatest of alumni of any restaurant that has ever existed – the likes of Eugene Callahan, Robbie Miller – all of a sudden, they’re all there in Belfast in 1991 – Neven Maguire; a real sense of excitement by 1991. In 1989, it’s quite interesting to look through our first book and see the people who were making cheeses for example, apart from the girls down in Cork, were, for the most part, blow-ins, German people, especially out in the West, and Dutch people, a significant number; and they weren’t Irish people, so the Irish hadn’t latched onto the quality of their ingredients, that again was one of the things Eddie did, was it wasn’t this sort of ‘everything from France is wonderful’, which was heretofore the mantra: everything from France was brilliant, and everything we had was second rate, he was one of the people who changed that.

The Irish had an inferiority complex about their own food. The French were brought up to believe they had the best cuisine in the world, the Italians were brought up to believe that their region was the greatest food in the world; but we had no confidence in our cooking altogether, absolutely none whatsoever – even though we had Declan Ryan, Myrtle Allen – they were so far out there for most people, that most people ate OK but increasingly badly as processed food took more of a market share. There’s a strong streak in Irish people where drinking was acceptable, but taking pleasure in food was not acceptable, considered bad manners. If you talked about food, you were considered really vulgar; you talked about how many pints you had on a Saturday night, but if you said actually, I think X place is better than Y, people would just look at you like you were completely insane. It was not discussed. It just wasn’t in the public agenda at all, it was part of that, if people talked about food at all they talked about Lent! Food as punishment, food as penance – fish on Friday; not because we get the best fish in the world because we have cold waters, but because you weren’t allowed to eat meat. So, one of the extraordinary things about Ireland in the past thirty years, people tend to focus on economics, but actually the extraordinary transition in ireland has been transformation from a self-denying society to an epicurean society, really. The food culture here is no longer denied.

Eddie was irresistible, he wasn’t taking no for an answer, and I think he was emboldened by being in West Cork because he’d be at these food fairs standing beside Ummera Smoke Salmon or Gubbeen Cheese, and he’d be saying: I’m as good as these guys – we belong together. That was the striking thing about west Cork in the 80’s was not just that you saw the construction of this artisan food culture, but that these people were so confident – exceptional people, very interesting people, who come in from the outside and come in with a different perspective, and asked – why aren’t you making the most of this? Eddie would have been emboldened by being surrounded with these people – he saw them all the time. By the difference with Eddie is, he didn’t have that outside perspective. He was from the country, but he just recognised that it was something important and he recognised that it had a story, it had a background, he didn’t represented himself as the person who created this, he represented himself as the person who represented the food – he was John the Baptist, he never presented as Jesus Christ, he was the messenger, and that gave him extra kudos, he wasn’t saying he made this out of nothing.

Gerry gave it a whole new context, Gerry ennobled it, Michael [Clifford] used it, but Gerry recontextualised it. And in a cultural sense I think that was hugely important. Gerry took this simple food and made it very special.

The hours and the miles that Eddie put in were formidable; and the other thing to remember in those days; when we were doing our first couple of books in ’89, there were no sources of information – there was no reliable guidebook to Irish food – it didn’t exist, and that was what we wanted to do, we wanted to write one, but it was very hard to find out who was good and who was doing something interesting, you had to keep knocking on doors. So, a lot of the time, Eddie would have turned up on doors and said I have a great black pudding and be told to F**k off – that’s for the dog! What happened with Ireland’s food culture was that in the 90’s, it snowballed and it changed everything.

APPENDIX 4 – BLOOD & BLACK PUDDING IN CONTEMPORARY FOOD WRITING

Irwin, F., (1949) The Cookin’ Woman, Edinburgh, Oliver and Boyd.

Sheridan, M., (1965) My Irish Cookbook, London, Frederick Muller Ltd.

Fitzgibbon, T., (1968) A Taste of Ireland, London, Pan Books (1st edn, 1970).

McKenna, J., McKenna, S., (1989) The Irish Food Guide, Dun Laoghaire, Anna Livia Press Ltd.

O’Shea, B., (1997) Pizza Defined, Durrus, Estragon Press.

Rankin, P., Rankin, J., (2005) New Irish Cookery, London, BBC Books.

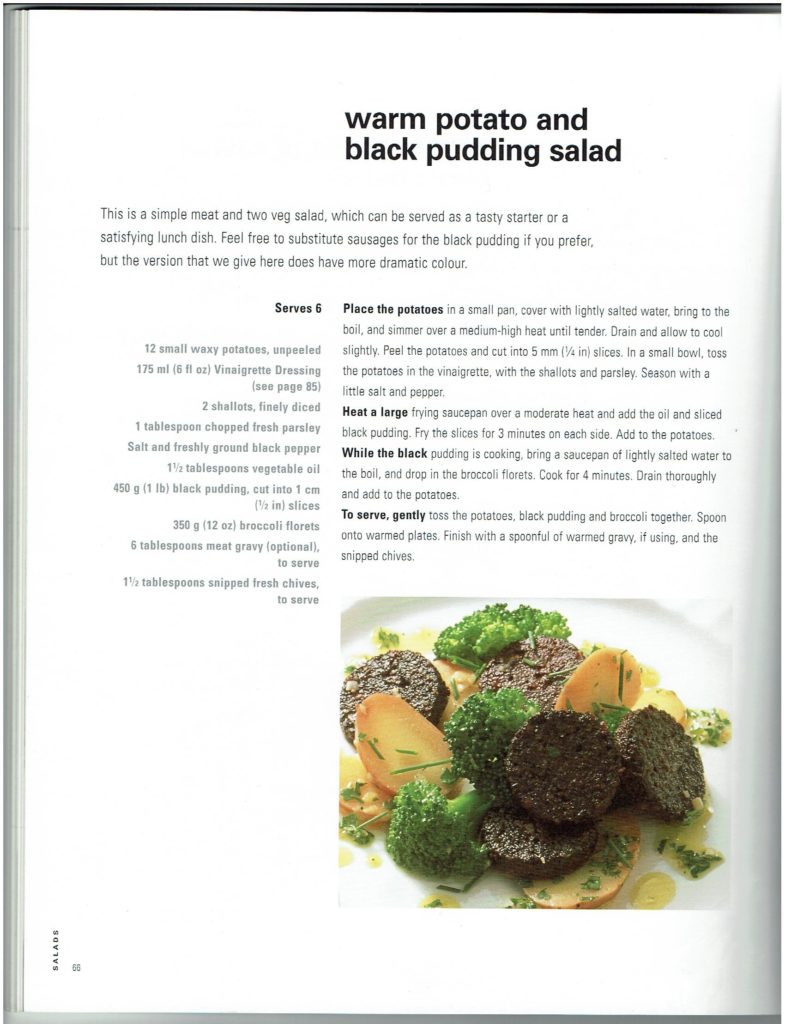

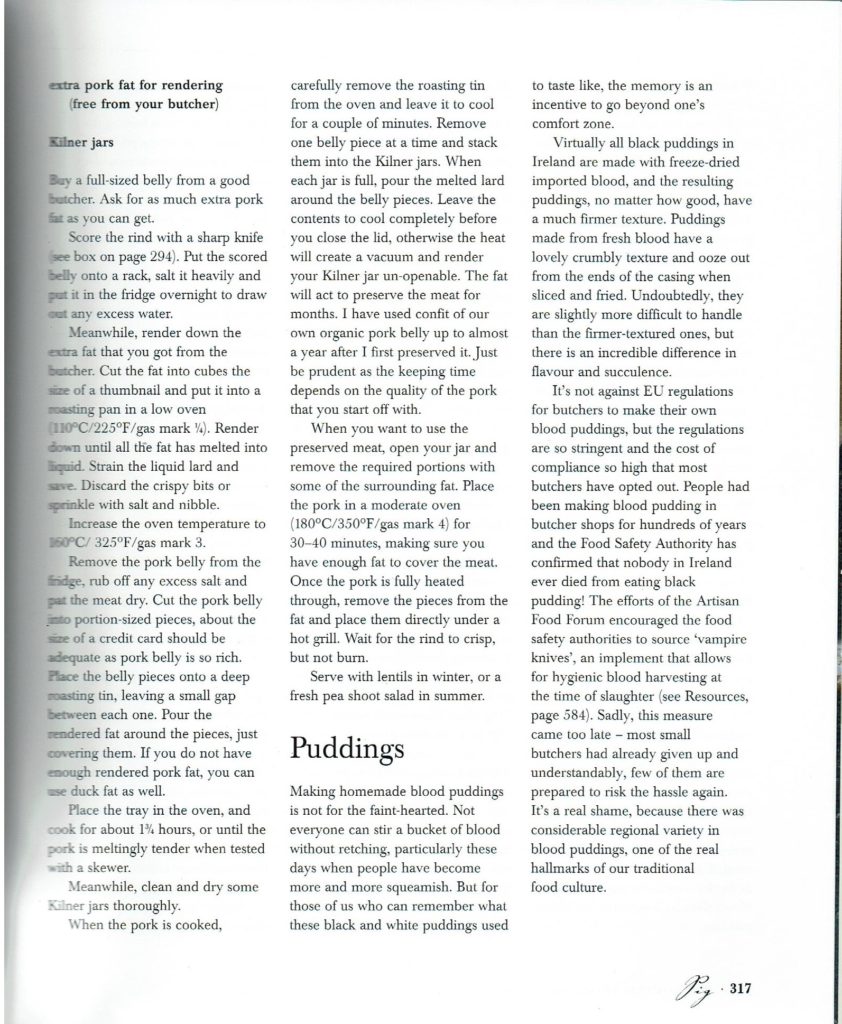

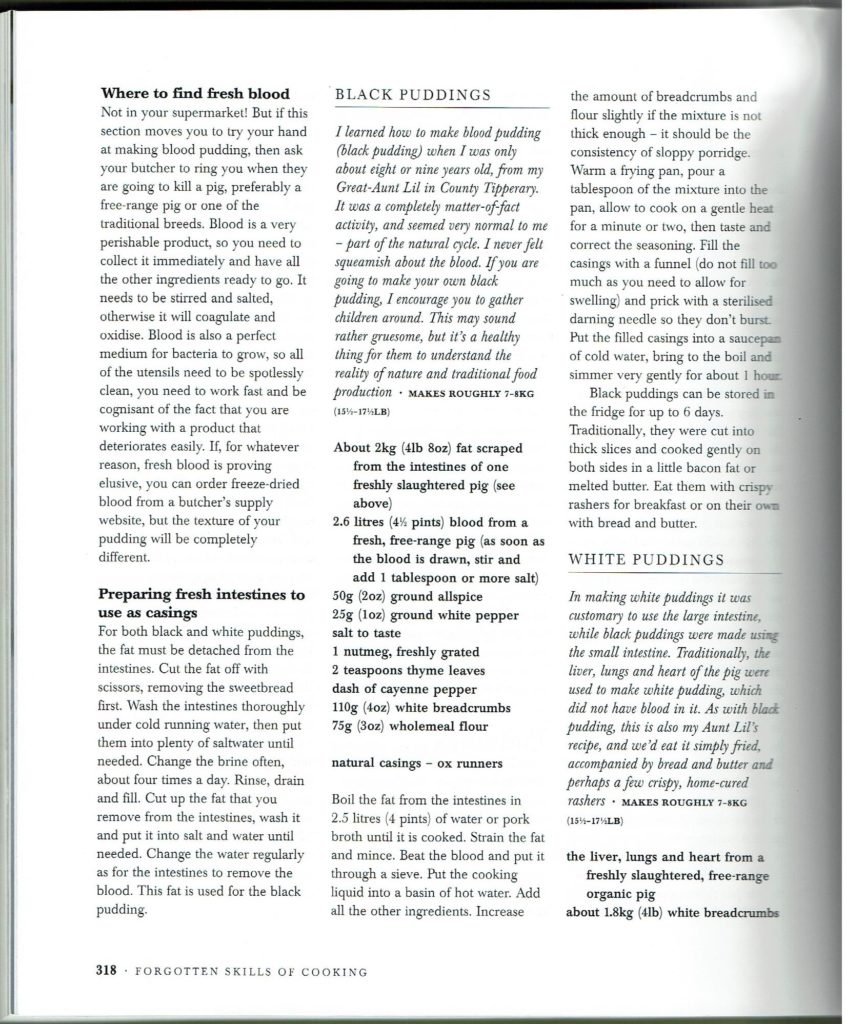

Allen, D., (2009) Forgotten Skills of Cooking, Great Britain, Kyle Books.

Blumenthal, H., (2009) The Fat Duck Cookbook, London, Bloomsbury.

Meller, G., (2016) Gather, London, Quadrille.

Lawson, N., (2020) Cook, eat, repeat London, Chatto & Windus.

McMahon, J., (2020) The Irish Cook Book, London, Phaidon.

FOOTNOTES

[1] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle, (Ireland, 1989). pp 204-205

[2] A. T. Lucas, Cattle in Ancient Ireland – Introduction, (Ireland, 1989) p 4.

[3] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle, (Ireland, 1989), p 221.

[4] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle, (Ireland 1989), p 219.

[5] H. V. Morton, In Search of Ireland, (London, 1930), p vii.

[6] H. V. Morton, In Search of Ireland, (London, 1930), pp 106-107.

[7] The Irish Free State was established in 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921.

[8] A reproduction image of Plate 18 is included in Appendix 2.

[9] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle (Ireland, 1989), p 218

[10] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle (Ireland, 1989), p 218.

[11] A. Wickham, Women Speak (Ireland, 2013), pp 77-80.

[12] Tómas Tuipéar is a local historian in Clonakilty.

[13] 3 litres of blood is the average yield from a modern day pig. Yield may have been less with older breeds.

[14] Hugh Maguire is the proprietor of the Smokin’ Butcher butcher’s shop and smokehouse in Co. Meath. Maguire produces a fresh pork blood black pudding.

[15] There are regional variations where black puddings are baked in a loaf tin instead of a ring. Despite not using intestine, or ‘pudding’, they are still referred to and marketed as black pudding.

[16] NFCS 15: 10-12. Collector: Rita Murphy, Cluain Fearta National School, Clonfert, County Galway, 1938. Teacher: C. Ó Ríoghbhardáin. [https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4583330/4580199/4587625]

[17] A complete transcribed account of this personal communication is available in Appendix 3, ‘Pers. Comms. 1’.

[18] A complete transcribed account of this personal communication is available in Appendix 3, ‘Pers. Comms. 1’.

[19] NFCS 731: 246. Collector: Joan Moran, (12), Tyrrellspass National School, Tyrrellspass, Co. Westmeath, 1938. Teacher: Mrs Payne. [https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/5009063/4982689].

[20] These and a selection of other recipes are available in Appendix 4.

[21] Clonakilty Blackpudding is the brand name. This is the intentional spelling.

[22] Clonakilty Food Co is the parent company which holds the brand name of Clonakilty Blackpudding and produces it at their manufacturing facility on Western Road, Clonakilty.

[23] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle (Ireland, 1989), p 201.

[24] This statement was repeated in three information interviews with local historians and extant relatives of Johanna O’Brien. An image in Appendix 1 is purported to be a photograph taken of Johanna O’Brien on the morning of the day she handed over her recipe to Philip Harrington. The image shows O’Brien holding two objects: a pair of eye glasses in one hand, and a piece of paper in the other. This piece of paper is widely regarded as containing the written down recipe. One informant relayed an account of the day Edward Twomey visited the home of Jimmy O’Brien, grandson of Johanna O’Brien, who had the image on the wall of the hallway, and contacted his two sisters, one who lived in Glandore and the other in Dublin, who both confirmed this story to Jimmy O’Brien and Edward Twomey, and who went on to comment that they always bought their black pudding from Harrington’s Butchers because this was their grandmother’s recipe.

[25] See Appendix 1 – Image 2

[26] See Appendix 1 – Image 3

[27] See Appendix 1 – Image 4

[28] See Appendix 3 – Pers. Comm 2 John McKenna.

[29] See Appendix 3 – Pers. Comm 2 John McKenna.

[30] A. T. Lucas, Blood as Food – Blood Drawn from Living Cattle (Ireland, 1989), p 222.

[31] McKenna, J., (2005) ‘Edward Twomey – John McKenna on the man who brought Clonakilty Black Pudding into the world’, Sunday Independent, 4th December 2005.