Reference Number: FL6802 – 115141319

Continue reading “The Social and Cultural History of Blood as Food in Ireland and its Role in the Formation of Identity for Clonakilty Blackpudding.”Deity to Hag. Women, Butter, Folklore, and the Image of Limited Good

Reference Number: FL6802-115141319

This essay was written for assessment in the Food, Festival and Folklore module of the Postgraduate Diploma in Irish Food Culture. It was submitted on 4th May, 2021.

Question: “Irish folklore, legends and popular beliefs often reveal something of the traditional Gaelic society’s relationship with and understanding of the natural world.” Discuss and illustrate the veracity of this statement, incorporating some examples from the National Folklore Commission, include a food element or food elements as relevant.

The importance of milk and butter in Ireland has been recorded throughout time and can be fully understood when viewed through the lens of two important days in the Irish calendar of customs: St Brigid’s Day and May Day, or Bealtaine. The early medieval Corpus Iuris Hibernici (Binchy, 1978) records milk and milk products as forms of tithe, land rents, punishments, and remediations, and dictating what milk and milk products should be appropriately used as hospitality depending on a visitors’ rank and standing. These legal tracts underpin the individual and communal importance of milk, its value and esteem, suggesting an inherent knowledge of the nutritional importance of milk in its various forms with the most nutritious of highest value and reserved for those of high status.

The 12th Century Aislinge Meic Con Glinne (Meyer, 1982) makes several references to desirable ‘white meats’ and demonstrates how five hundred years after the creation of the Corpus Iuris Hibernici the importance of milk was evident in the everyday diet of the Irish. Lucas, (1960), wrote how: “Milk constituted virtually the sole food of the ordinary people during the summer,” that cows were kept for their milk, that milk was considered “food for guests” and that a cow would only be killed for meat once deemed too old to yield anymore milk. Milk was an important and valuable source of food in medieval Ireland, something that has persisted to the present time. Those who eked out an existence from subsistence farming knew as much, and that: “The prosperity of the coming year hung on May Day.” (O’Gealbhán, 2021).

Much depended on acquiring milk in sufficient quantity, also its quality for making good butter (Lysaght, 1994). Dairying work, calving, milking, and butter making fell to the women of the farm, a likely extrapolation of the legend of St Brigid. St Brigid, (also Bríg, Brighid, Bríd, Bridget and Bride), one of Ireland’s three patron saints, is an influential figure in pagan and Christian lore whose feast day occurs on 1st February, marking the first day of spring in Irish custom, also known as St Bridgit’s Day, Imbolc or Oímelg in ancient Irish, a word that literally translates as ‘lactation’. O hOgáin (2006) says:

“St. Brigid has always been regarded as the special patroness of farm animals and crops […] portrayed as having the power to multiply such things as butter, bacon, and milk […]”

In Irish folklore, tangible boundaries play an important role in separating the intangible boundaries between worlds. O hOgáin goes onto say accounts from Medieval hagiographies “detail that Brigid was born as her mother brought milk into the druid’s house at sunrise – the mother had one foot outside the threshold and the other foot ‘neither without or within.’” The inclusion of the detail around sunrise speaks to the folklore belief that magic was at its most potent on the eve of a feast day expounding belief that boundaries, and events that happen near boundaries, are powerful. A third boundary is in play in this account: that between the inner world and the outer world, experienced as childbirth. This trinity of boundaries reinforce a portrayal of Brigid as a woman of power, supernatural or otherwise. The trinity appears again as the three patron saints of Ireland, Patrick, Brigid and Colmcille. O hOgáin provides further examples where boundaries and trinities are associated with St Brigid:

“Foremost among the customs was that of the Cros Bhride (Bridhid’s Cross), […] in Ulster a simple three-legged type was sometimes used for cow byres. Equally prevalent was the custom of leaving a piece of cloth outdoors from sunset to sunrise on the eve of the feast in the belief that the saint would touch it and thus confer on it protective and curative properties. […] A more general practice was to include the residue from the making of Brigid’s Crosses in new spancels for the cows, so as to protect them during the ensuring year.”

St Brigid is such a key figure in Irish folklore to the extent Christianity could not supplant her, (O hOgáin, 2006) instead, realising Brigid as a saint of importance in day-to-day life of the rural peasantry and enfolding that into Christian teaching. This straddling of belief systems re-emerges at Bealtaine and illustrates how the link between Brigid and Bealtaine creates a continuum in what was a pivotal time of year in terms of survivalism while blurring the boundaries of how to celebrate deities and customs: the festival of St Brigid is religious whereas the festival of Bealtaine is pagan. Both are associated with nature in as much as they are markers of significance in the seasonal calendar, it is the May Day festival of Bealtaine where symbolism, beliefs, and connections with nature and preternatural peak and are heavily associated with the feminine: in symbolism of fertility and abundance, but also witchcraft, charm setters, Bean Feasa; coinciding when milk is at its richest and butter making, the engine room of the domestic economy, is in earnest. Such depictions of women and their influence on the natural world are two sides of the same coin and can be interpreted either as locating women in positions of power or highlighting their precarious position in traditional Irish society.

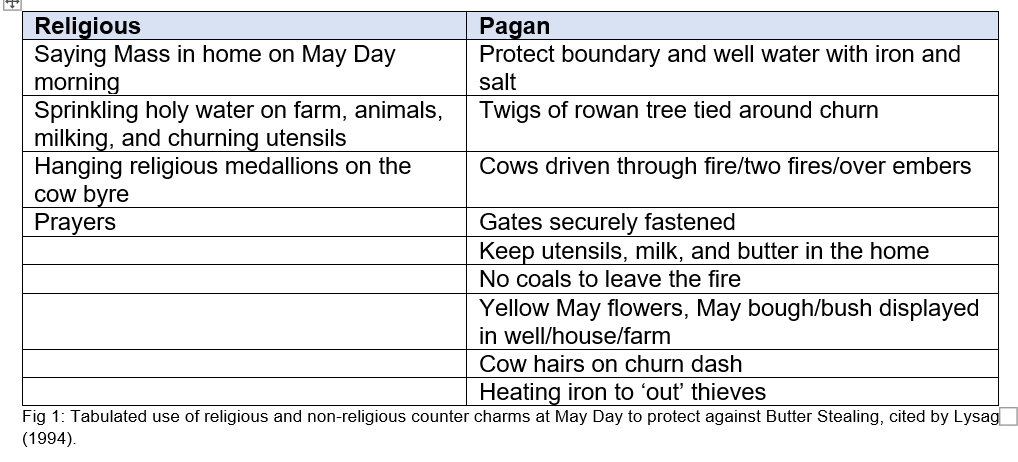

Folklore is plentiful around Bealtaine accentuating a vernacular anxiety in anticipation of prosperity or failure based on the ability of women to make plentiful and good butter. Given the significance of butter to the rural Irish in actuality (the difference between full bellies and not) and the link between dairying and beliefs (both pagan and Christian), it is unsurprising that a complex system of customs, beliefs and superstitions to protect butter and milk ‘profits’ from theft during the festival of May, (Lysaght, 1994), developed “as a way to explain the inexplicable,” (Mac Néill et al, 1977), and which pervade in Ireland until 1940’s, only waning with “the coming of the creameries [which] put an end to the fear of butter-stealing […] In their time, nevertheless these things must have been the cause of grief and of terror to many, and their passing away is nothing but a blessing,” (Danaher, 1964).

St Brigid, Bealtaine, and Sympathetic Magic

St Brigid’s Day marks the beginning of spring and Bealtaine marks the beginning of summer, (Danaher, 1959) both connected to the importance of dairying to the rural (peasant) classes. Superstitions are heightened at Bealtaine, a fretfulness about protection at a liminal time when the veil between this world and the other world is at its thinnest and things of value become vulnerable to malevolent magic. This is in contrast with Samhain when liminal time also occurs but is associated with welcoming beings and visitations from the other world.

The folklore, beliefs, and customs prevalent at St Brigid’s Day and Bealtaine differ but are not mutually exclusive. The belief in the employment of sympathetic magic is widespread at Bealtaine, especially in relation to butter protections, stealing and remedy. Frazer, (1925), identifies two branches of sympathetic magic: Homeopathic (like for like) and Contagious Magic (continuous effect) and says: “the laws of sympathetic magic are not limited to human action but are universal in application.” This can be seen in some of the protective measures employed during Bealtaine to prevent butter stealing. Taking a lit coal from the fire; placing yellow blooms at boundary places; tying the butter churn with rowan branches; skimming May morning dew, water from the surface of a well or streams and rivers; or driving an iron nail into the bottom of the butter churn – all of which are human actions. Driving cattle over embers or “between two fires”; smoke escaping from the chimney, or the motif of the changeling hare suckling from a cow’s udder, could all be universal application where other aspects of nature are employed: the elements, other creatures of the natural world, etc. (Danaher, 1964; Lysaght, 1994; O’Gealbhan, 2021; National Folklore Collection).

“Magic is always considered art, not a science” (Frazer, 1925), that “the principles of association are excellent in themselves, and indeed absolutely essential to the working of the human mind.” Magic is pre-science and reiterates O’Neill’s statement that it provided a framework for viewing and understanding the world at a time when the inexplicable and science were strangers to each other. At Bealtaine, all thoughts are occupied by butter making and the magic, malevolent or benevolent, that might be performed in either the protection of the butter profits or the stealing of them. Lysaght (1994) notes that the “profit thief was invariably believed to be a woman,” and as women were responsible for butter making and that good quality butter could produce sufficient income for the year ahead, Lysaght also suggests that this pressure to provide may have given rise to the notion of The Butter Thief:

“Since milk and butter production were the responsibility of the women of the community, and since they no doubt wished to be as successful as possible in this vital undertaking, they were, of course, in competitions with each other.”

Lysaght goes on to state that women farmers or any woman who was alone, independently, or otherwise, and in some way “socially unsupported” were also viewed with suspicion. By Bealtaine, women have transgressed from being associated with a goddess figure of abundance and miracles, to an association with malevolent charms and spells capable of thievery; from a persona of captivating beauty to one of an old hag possessed of magic. O’Catháin (1975) goes further and states: “even a little special or occult knowledge, whether for good or evil, perhaps, even an innocent expertise in the medicinal use of herbs, for example, was sufficient to set any woman apart and qualify her as a ‘cailleach’ or a ‘máistreas’…” When much depends on butter, the status of women in society is on shaky ground, and this is emphasised further in the benign consequences of men in relation to butter stealing: men ‘accidentally’ steal the butter seemingly without understanding the effect of their actions or incantations; and whereas women must employ sympathetic magic to make good their thievery, men simply return what is considered excess to their share of the butter profits.

The National Folklore Collection of Ireland holds 13,767 mentions of butter in the transcripts of the Manuscript Collections, and includes accounts of customs, beliefs, stories and superstitions of butter thefts, sympathetic magic applied, and the differences between women and men in relation to butter stealing. Even the material culture used in milking, skimming and butter making is catalogued such is their importance in the domestic economy, but also because of their vulnerability to sympathetic magic.

Danaher (1964) noted that milk, butter, and cream all remained vulnerable until taken to market. The use of salt in butter was a popular method of protection especially when butter left the house; yet salt is an excellent preserver, something that would have been well known in the context of meat and fish curing for winter stores. Use of salt in butter is an excellent example of where the act has a basis in what we now understand as science, but at the time adding salt to butter was used to promote good luck – a preservative, nevertheless. Butter was seen as particularly vulnerable to the actions of hags but also “the Good People”, (Danaher, 1959) or fairies, and various counter charms could be employed to protect butter from their malevolent ways. The use of hot iron in milk when butter wouldn’t come is another example where pre-scientific thinking was deployed in the eradication of spells cast by the wee people, but that could now be explained by the cream being too cold to churn into butter. The belief here is that fairies are vulnerable to iron, one of several protections often cited in the NFC transcripts used against the malevolent magic of fairies, including: fire, salt, running water, and faith (Lysaght, 1994). Other protections are tying red ribbons; use of hawthorn or rowan twigs, wearing one’s clothes inside out, or keeping herbs or yellow flowers in a pocket.

Appendix 1 details a few short examples from the NFC of the use of such items in the protection of cows, butter makers and butter churns. A theme that reoccurs is a belief that butter could be taken, stolen off the milk or the churn; and reinforces the connection between supernatural beings, especially fairies, and abduction (O hOgáin, 2006), or that butter profit could be stolen by an act of sympathetic magic, with or without incantation, such as skimming dew from grass on May Day morning with a rag or a stolen spancel. An incantation combined with a reddened iron coulter was thought highly effective in the return of stolen butter profit:

Come butter, come,

Come butter, come,

Peter stands at the gate

Waiting for a buttered cake,

Come butter, come.

And if the milk has lost its good qualities by means of incantations,

it immediately turns to excellent butter. (Crofton Croker, 1824)

The Image of the Limited Good

Folklore beliefs and customs associated with butter have a close connection to the theory of “limited good” in peasant communities, as documented by Foster (1965):

“Peasants view their […] total environment exists in finite quantity and are always in short supply, as far as the peasant is concerned. […] There is no way directly within peasant power to increase the available quantities.”

In a small community, there is an expectation that each person will have a share of the total amount of butter produced relevant to their position (e.g. number of cows). Should one person suddenly lose the ability to make butter while another suddenly is able to produce more than usual, it upsets the perception of a proportionate share in a limited good – e.g. butter. Foster argues that such communities are closed, therefore any perceived gain at the expense of another’s loss is easily deduced and blame levelled accordingly. The notion of Limited Good “is seen as […] the supreme threat to community stability, and all cultural forms must conspire to discourage changes in the status quo.” When much depends on butter, and women in a closed community are solely responsible for that industry, the competitiveness that Lysaght (1994) identifies between women is intensified; and in the knowledge vacuum created by pre-science, the use of magic and supernature to explain the inexplicable, as O’Neill (1977) puts it, supports belief in malevolent magic and the use of counter charms to undo its effects, thus justifying a belief in butter stealing. Furthermore, a reinforcement that magic ‘happens’ with respect duly accorded to the observation of the folklore, charms and belief structures associated with it.

The Church’s acquiescence to assimilate the cult of St Brigid in its teachings finds itself involved in religious exorcism of pagan spells and fairies, with those afflicted mixing religious and pagan lore and beliefs in banishment of wickedness and malevolence:

Folklore, as it pertains to butter stealing, becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts; and speaks to the societal pressure of women in their role as mistresses of an important facet of the domestic economy. It demonstrates how well women in traditional Gaelic society understood the importance of the dairying season – not only for the survival of the family, but also as it pertains to her position in society. Women did not possess such privileges as ownership and status and their position was precarious as a result, therefore it is possible that use of folklore beliefs were deployed as a tool to shift focus away from any perceived inability to provide. The start of dairying season is full of promise, enhanced by the deity status of St Brigid; but come Bealtaine, the milking woman needs to be successful in her endeavours, less she be deigned useless at best; a hag at worst.

Word Count: 2731

Appendix 1: Excerpts from the National Folklore Collection (NFC) referencing folklore, customs, beliefs and superstitions around butter making, butter stealing, accidental butter stealing, charms and counter charms, and material culture.

A. Examples of Charms and Spells

A.1 NFCS 0208: 142; Denis Flynn, Inchinarihen, Co. Cork. Collector: Denis Flynn, Barrlinn National School, Co Cork, 1938. Teacher: Máire Ní Chruadhlaoich. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4921577?pageNum=142

Piseog’s Connected with May Day

Long ago people’s butter used to be “taken” from them, that means some bad minded neighbour used to put bad eggs or something in the dairy. Some people used to go to the priest to pray for them so that they might get their butter back. This is a piseog connected with May Day, “that if you make butter on May Day and if you keep some of the butter in the house for the year, nobody could steal your butter from you. Many people here made it their business to make butter on May Day and they carefully preserved it for the year. Then nobody would have the power to “carry” the butter.

A.2 NFCS 0094: 285; Charles Daly, Belcarra, Castlebar, Co Mayo. Collector: Charles A. Daly, Belcarra (Buachaillí), National School, Co Mayo. Teacher: Seosamh Ó Heireamhóin. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4427830?pageNum=285

Taking the Butter off the Milk

Long ago if you went into a house and a churning to be going on you should put a coal under it and a grain of salt into it, and if you did not that person would never have a bit of butter out of it. It happened that a red haired woman went into this house, while a woman was churning and took all the butter on her. For months she had no butter until at last one day a priest, having come into the house, and she told him of how she had been churning for months and never got a bit of butter. He told her to go to the red haired woman and tell her she was down and out and would she kindly spare a bit of butter. She having done as he had commanded her and she always had enough of butter from that day forth.

A.3 NFCS 0123: 183; Rose A Henegan, Tumgesh, Co Mayo. Collector: Rose A Henegan, Tomghéis National School, Co Mayo. Teacher: M. Ó Casaide. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4427956/4360952/4465345

Butter Making – A story – Superstition

There was once a woman on the border of our village, who was supposed to be on the pastures on a May morning before the sun got up and before any smoke came out of any of the chimneys, to pick a certain herb and to skim the well where people went for water to make their butter. It was said that she sold a great amount of butter each week, from one cow and some people said that she used to say “the butter of the village for me”.

Rose A Henegan.

B. Examples of Sympathetic Magic employed in Butter Stealing

B.1 NFCS 0050: 159-160; Michael Kelly, Reyrawer, Co Galway. Collector: Eileen, Réidh Reamhar National School, Co Galway. Teacher: Seán A. Mac Fhloinn. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4583308/4578397

Biddy Early and the Butter

If Biddy Early came into a house and the people churning she would take the butter from them. One time there was an old woman out in Clare. She had the finest “bawn” of cows you could lay eyes on and during one week not a bit of butter would come in the churn if she was churning till morning. Nothing but froth and an awful smell out of it. There was a calf after dying on the woman’s neighbour. Biddy Early had the dead calf dug up and buried in the woman’s land. While the dead calf was in the land she couldn’t get any bit of the butter. She told the priest about Biddy Early and he hunted her out of the place. From that time Biddy Early lived near Feakle and before that she lived near Lough Grainne.

Biddy Early used often go begging house to house. One day, there were three men coming home form digging potatoes with their spades on their shoulders. They met Biddy Early and as she passed them by, one of them saw a briar stuck to her shirt and trailing after her. He took down his spade, cut off the end of the briar and pure new milk ran out of the briar. That night the spade was stolen from him and he said it was Biddy Early stole it.

B.2 NFCS 0637: 153; Cappoquin, Co Waterford. Collector: N/A. Teacher: An tSiúr M. Teresita, Clochar na Trócaire, Ceapach Chuinn. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4428096?pageNum=153

Butter-Making

My mother always put a spark of fire under the churn or into it, to keep away evil.

The Co. Kerry spailpíns used to come here to dig the potatoes. Five or six were there and the day came very wet, and they were all inside. The mother said they could make the butter, and if they were not at it yet, they couldn’t get it all to turn. One of the men said “I’ll soon find out who is taking it. He reddened the sock of a plough and started beating it with a sledge and it started to blaze so much that they all ran out, they thought he was bringing the devil out of it, and what did they see but a woman walking down the road who had been sick for a long time. I saw her myself. After that they made the butter. I believe myself that the evil spirits were handed down from generation to generation. They can do these things.

B.3 NFCS 1026: 220-221; Mrs Mac Grory (30), Ballymunterhiggin, Co. Donegal. Collector: N/A. Teacher: Eibhlis Ní Mhathghamhna, Loughill National School, Co Donegal. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4428250/4388407

Getting Back Stolen Butter

James Loughlin was coming from town one morning at three o’clock. As he was passing along a lonesome road he saw two girls in a field throwing a ball or yarn from one to the other. He stood and watched and soon the ball of yarn was thrown over the ditch and he caught it. He brought it home and threw it up on the “hure” [?] over the fire. Sometime afterwards James get a hole in his stocking and his wife had no yarn to mend it. James thought of the yarn on the “hure” and got up to take it down. When he found it, it was covered with butter. The two girls were supposed to be stealing the butter from cows which were in the field. and get a horse shoe made. The iron must only be heated once. Take it home and when you start churning again put it under the churn. During the churning moans and cries will be heard outside and the butter will be given back. The shoe is supposed to burn the person who stole the milk ad she repents and gives it back.

B.4 NFCS 1026: 128; Mrs F Miller (30), Ballyshannon, Co Donegal. Collector: N/A, Loughill National School, Co Donegal. Teacher: Eibhlis Ní Mhathghamhna. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4428250/4388407?pageNum=128

Butter Stolen Off the Churn

Butter is sometimes stolen off the churn. When this happens a person churns for hours and hours and still no butter appears. To get the butter back procure a box of pins and place them beside the fire. Close the door and do not open it no matter what knocks or noises are heard outside. Then continue churning. Many knocks will be heard and many cries and moans. Before long the butter will appear as usual. Out of the box by the fire the pins will have disappeared and drops of blood will be seen on the doorstep. These pins are supposed to stick in the person who has stolen the bitter and this person is supposed to repent and give it back. Only special people will have this power of bringing back the butter. The person is usually a woman. The above is a description of what she tells one to do in a case of stolen butter.

B.4 NFCS 0147: 40; Ballna, Co Mayo. Collector: N/A, Béal Átha ‘n Fheadha, Co Mayo. Teacher: D. P. Ó Cearbhaill. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4428053?pageNum=040

This entry is unusual in that the butter is stolen by a man, but it is unclear if the act was accidental, or the appearance of butter thereafter expected or a surprise.

Taking Away the Butter

A man went into a house where the churning was going on, and took a lighted sod to bring to the bog. The woman continued the churning but got no butter. The man when leaving the bog threw the coal in a bog hole and when the man returned to the bog next morning the quenched coal and they woman’s butter were side by side in the bog hole.

C. Examples of Accidental Stealing of Butter by Men

C.1 NFCS 0190: 19-20; William Clancy, Aghanlish, Co Leitrim. Collector: Pádraig Ó Gallchobhair, Ahanlish National School, Co Leitrim. Teacher: Pádraig Ó Gallchobhair. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4602723/4598452/4626435

Taking the Butter on a May Morning

Clancy was profound believer in charms spells superstitious practices. He lived in the downland of Drumcashel in his early days. It was a thickly populated townland and the Clancy family resident was in the centre of what was almost a village. One may day morning he was return from a wake just as the morning was breaking. As he approached the cluster houses he observed an old woman of the place who was looked upon almost as a witch traveling swiftly from house to house. From the eve of each house she pulled a few straws and not ceasing till she had finished every house and pulled a few straws from each. By the time she had a finished she had a fairly good sized bunch of wisps in her hand which bunch she on reaching her house stuck into the thatch just over her own door and then went in closing and bolting the door when inside. the “master” waited for some time till he felt she had retired to bed then he noiselessly crept up to the door of the woman’s house and extracted the bundle of straws she had stuck in and got away as noiselessly as he came. When he reached his own home he stuck the wisps into the eve of his own house and went to bed.

Next day his mother started to churn. After a time she found it impossible to work the “dash” in the churn. She removed the lid to see what was the matter and to her surprise found the churn packed with butter. This she removed and re-started the churning to find the same thing repeated. She continued taking butter from the churn till every available vessel in the house was filled. Soon the news spread of the neighbours churning for hours without a trace of butter appearing on the milk. When the “Master” returned from school and heard of the wonder he took the magic wisps from their hiding place and returned some to each house visited by the witch woman. He also made his mother share the butter amongst the victims. After that things went on normally.

C.2 Accidental Butter Stealing, Use of Incantation, Religious Interception

NFCS 0409: 107-110; Mrs Mary Kirby (72), Kilcarra Beg, Co Kerry. Collector: Bridie Flaherty, Dromclough (C.), Co Kerry. Teacher: N/A. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4613725/4613155/4643643

How People Through Witchery Stole Butter

About fifty years ago a young student lived near Rathea. This time he was home for the Easter holidays, and it happened that he was invited to a friends house to a party.

He was coming home when the sun was rising on May morning. He was coming through a field and he was passing the boundary going into his own farm. He saw an old woman up on the ditch between two white thorn bushes with a reaping hook in her hand.

Every time the wind would blow she would slash the hook towards his neighbour’s cows, and said “half of your butter to me.” The student was surprised, and every time she said “half of your butter to me”. he used say and “the other half to me.” When the sun rose she went home and he went home too.

The next time his mother was making butter at home she couldn’t stir the barrel it was so packed. She was surprised, and wondered where she got all the butter. The student heard her talk about the butter, and said “Mother such a thing” telling her about the woman.

The next day they went to the woman whom the butter was carried from. She had no butter. They told her what happened, and the Student said he was only codding. Then they went and told the priest and the old woman was found out and beaten, and the woman got back her butter again.

That Student was a priest for a long time in America, but now he is dead. His name was Father O’Leary native of Rathea Listowel Co. Kerry.

C.3 Accidental Butter Stealing, Use of Incantation, Religious Interception

NFCS 0228: 76; Thomas Brady, Ballyduffy, Co Longford. Collector: N/A, Druim Bréan Lios National School, Drumbreanlis, Co Leitrim. Teacher: Eibhlín Nic Ghuidhir. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4658459?pageNum=076

Beliefs Concerning Taking of Butter by Witchcraft

A boy named Masterson living in the townland of Enaghan near Arva was minding cows in Cordonaghy (a town land also near Arva) about sixty years ago. He saw a woman come to a well, take off all her clothes and go into the well. She started to teem the water out of the well with a trencher while saying “the whole of it to me”. The boy not understanding that she meant any harm said “the half of it to me”. When he went home his mother churned and found out that she got as much butter from the churning as she would in the ordinary course of events have got from twenty churnings. She told the priest and he said the boy was not accountable since he meant no harm and he blessed the well that the woman was in.

A lot of people in the town land of Cordanaghy failed to get butter from their milk for some time before this but got it after the well was blessed.

In the town land of Fahora lived a family named “Smith” 50 years ago.

They could not get butter from their milk for a considerable time. They were told by someone to milk a cow belonging to all their neighbours in turn and when they’d mix the milk of a cow belonging to the person who practised the witchcraft with the milk of their own cows they’d get back the butter. They milked several cows but without effect until they milked the cow belonging to a man named McNaboe. When McNaboe’s cows milk was mixed with that of their own cows and churned they got a copious supply of butter. They had no hesitation then in saying that the McNaboe family practised witchcraft and made the story public. The McNaboes denied they were guilty and came and took an oath at Moyne Chapel that they were innocent.

References & Bibliography

References

Figure 1. Lysaght, P., (1994) ‘Women, Milk and Magic and the Boundary Festival of May’ in Long, L., eds. Food and Folklore Reader, 1st edition, Bloomsbury Academic.

Bibliography

Binchy, D. A., ed. (1978) Corpus Iuris Hibernici, 1st edn, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Danaher, K., (1964), Irish Customs and Beliefs, Mercier Press.

Danaher, K. (1959) ‘The Quarter Days in Irish Tradition’, Journal of Scandinavian Folklore, Vol. 15, pp 47-55.

Foster, G. M., (1965) ‘Peasant Society and the Image of Limited Good’, American Anthropologist, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 293-315.

Frazer, J. G., (1900), The Golden Bough A Study in Magic and Religion, abridged edition (1994), Macmillan & Co.

Lysaght, P., (1994) ‘Women, Milk and Magic and the Boundary Festival of May’ in Long, L., eds. Food and Folklore Reader, 1st edition, Bloomsbury Academic.

Lucas, A. T., (1960) “Irish Food Before The Potato”, in Gwerin: A Half-Yearly Journal of Folk Life, 3:2, 8-43.

Meyer, K., (1982), Aislinge Meic Conglinne, The Vision of MacConglinne, a Middle-Irish wonder tale, 1st edition, David Nutt London.

O’Catháin, S., O’Flanagan, P., (1975), The Living Landscape Kilgalligan, Erris, County Mayo, 1st edn, Comhairle Bhéaloideas Éireann An Coláiste Ollscoile, Dublin.

Ó hEochaidh, S., Mac Néill, M., Ó Catháin, S., eds (1977) Fairy Legends from Donegal (Síscéalta ó Thír Chonaill), 1st edn, Dublin, Comhairle Bhéaloideas Éireann.

O’Gealbhán, C., (13th April, 2021) Lecture Presentation.

O hOgáin, D., (2006) The Lore of Ireland, An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance, The Boydell Press.

The National Folklore Collection – multiple entries, refer to Appendix 1.

Crofton Croker, T., (1798), Researches in the south of Ireland illustrative of the scenery, architectural remains, and the manners and superstitions of the peasantry, with an appendix containing a private narrative of the rebellion of 1798; introduction by Kevin Danaher, Irish University Press, 1969, [online] , available: https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E820000-001.html